The Use of Unorthodox Training Methods for Prehospital Trauma Care

Jonathan McCarthy, SOCM; Michael J. Lauria, MD, NRP; Andrew D. Fisher, MD, MPAS*

Originally published in the Journal of Special Operations Medicine (JSOM). 2022 Sep 19;22(3):29-35. doi: 10.55460/AQU3-F0UP. PMID: 35862849.

ABSTRACT

Prehospital trauma care guidelines and instruction have advanced significantly over the past 20 years. Although there have been efforts to create a standardized approach to instruction, the use of unorthodox techniques that lack supporting evidence persists. Many instructors use unrealistic scenarios, “no-win” scenarios, and unavoidable failing situations to train students. Doing so, however, creates student confusion and frustration and can result in poor skill acquisition. These training techniques should be reconsidered, with focus placed instead on the development of technical skills and far skill transfer. Knowing when to apply the appropriate type and level of stress within a training scenario can maximize student learning and knowledge retention. Furthermore, modalities such as deliberate practice, cognitive load theory (CLT), and stress exposure training (SET) should be incorporated into training. To improve delivery of prehospital trauma education, instructors should adopt evidenced-based educational strategies, grounded in educational and cognitive science, that are targeted at developing long-term information retention as well as consistent, accurate, and timely life-saving interventions.

Introduction

Over the years, prehospital, combat-oriented medicine has embraced evidence-based medicine and pursued scientific endeavors to provide better patient care and improve outcomes. However, the degree to which there has been an equivalent reciprocating effort to apply an evidence-based approach to training and educational modalities remains in question. It is a particularly salient question given that our communities have developed standardized, high-quality guidelines for Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC), and Stop the Bleed (STB).

Notable concerns exist regarding the training of individuals utilizing “unorthodox” methodologies as well as adherence to such time-honored catchphrases as “train to failure” or “you don’t have to practice to be hard.” Knowingly allowing students to fail, purposefully applying excessive stress to novices, ignoring the cognitive science literature regarding skills acquisition, or conflating being “cool” with effective training techniques is a disservice to medic and layperson trauma training. There is a time and place for training that inculcates an understanding of and develops resilience toward combat stress. However, this should be done in a measured, deliberate manner with the appropriate group of learners. By and large, effort should be expended to teaching high-yield, evidence-based tactical medicine using evidence-based techniques and modalities.

Pitfalls and training failures may be readily identified in TCCC, TECC, and STB training techniques encountered in military and civilian circles. The effects of environment on learning and skills development are ingrained in cognitive psychology and neuroscience. It is critical to understand the paradigms regarding the incorporation of stress into training. We seek to offer methods for instructors with novice understanding of these areas to best optimize the learning environment for long-term retention of knowledge and skills, as well as to facilitate the application of these skills in novel situations.

Discussion

Too Much, Too Soon: Effects of Environment

on Learning and Skills Development

Teaching critical combat medical skills under simulated combat conditions is often a goal of high-fidelity training in the military. This type of training is reasonable and can be helpful, but educators and training staff need to exercise caution regarding trainees’ command of the material, the level of environmental stress present, training complexity, and the time course in which stressful stimuli are applied.

Drills such as live fire exercises while students practice packing a wound appear at face value to be “high speed.” However, when it comes to developing accurate and timely technical skill execution, these drills may not help and could be detrimental to students’ learning. More specifically, whether they will be effective as learning tools is highly dependent on a learner’s skill level. Objective measures that define experience or specific, objective criteria that characterize a novice or expert in a given field vary significantly. In general, a novice is an individual with little or no knowledge or experience in a particular domain. Conversely, an expert is an individual with significant or comprehensive knowledge of experience in a particular domain. An important difference between novices and experts, as it relates to technical skill execution, is the individual’s degree of constructed automaticity (commonly referred to as “muscle memory”), fidelity of his or her mental representation of the task, and the ability to pattern-match and recognize indications or obstacles to task completion. For example, inexperienced or novice medics may have never placed a tourniquet on a real patient. As such, they have to use more cognitive resources to control their attention, think about executing the correct steps of the procedure, and consider any challenges or difficulties with the procedure. The addition of extrinsic stressors such as yelling, gunfire, or

direct disruption of the activity from an instructor can create an overly stressful environment for students who have not yet developed competence with certain skills.

Although training to manage the stress of combat, in general, is a reasonable and potentially helpful paradigm, it may not be useful when it comes to the initial acquisition of fundamental technical skills. Stress is a process whereby environmental demands evoke an appraisal mechanism in which perceived demand exceeds available physical and mental resources, resulting in undesirable physiological, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. This does not always facilitate effective learning. A stressor that activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is moderate, germane, and specific to the task at hand during an educational activity (e.g., the intrinsic stress of applying a tourniquet with ongoing simulated hemorrhage) and may be helpful for learning. Specifically, there may be enhanced memory consolidation and future retrieval of information. However, stressors that are not directly related to learning goals (e.g., extrinsic stressors) or severe stress can have the opposite effect. These stressors detract from the brain’s ability to store information in long-term memory, which has a negative effect on a learner’s capacity to recall information and apply it in the future when needed.

Ultimately, the goal for technical skill development in TCCC, TECC, and STB is to be able to reproduce skills quickly and efficiently when someone is seriously injured in a stressful situation. This occurs best when an individual develops automaticity of a particular skill. Automatic psychomotor skills require substantially fewer mental resources and are reliably reproduced during periods of high cognitive load (such as when one experiences significant stress). Ingraining and automating the correct psychomotor program is critical. This requires application of novel information and retrieval of knowledge from memory. Therefore, if a trainee was taught during a didactic session where to place a tourniquet in relation to an injury and how best to tighten the tourniquet, he or she would have to retrieve this information and apply it. However, stress can also inhibit effective information retrieval. Furthermore, excessive stress seems to switch the system’s underlying learning and memory from a more “cognitive” memory system in the hippocampus to a more rigid “habit” memory encoded in the dorsal striatum. This switch results in cognitive perseveration: continuing or repeating a given action or plan that one has recently used or previously applied. As stress increases and cognitive faculties deteriorate, individuals may continue trying the same unsuccessful solution despite clear evidence of its failure. They default to what is known or familiar in times of stress. Unfortunately, when trying to apply new information or solve a novel problem, trainees might fail to explore novel solutions, apply learned information, and develop effective technical skills. Thus, overly stressful drills potentially reinforce old, bad habits and perpetuate incorrect techniques.

On occasion, instructors have had trainees practice life- saving combat skills with live gunfire, live explosions, or other noisy distractions in close proximity. Although the intention of training techniques such as these is to get students conditioned to working with distractions, these modalities may have unintended consequences. Situational awareness is the perception of the elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status into the near future. Expert medics, or even those with some experience, might recognize the sound of close and effective gunfire, understand its significance, recognize they are in a Care Under Fire situation, and take appropriate action (e.g., identify threats, immediately return fire, take cover, instruct the casualty to return fire if combat effective). Novices are easily overwhelmed by stimuli, may not be able to gather or recognize critical data, understand what it means, and formulate the appropriate response. Instructors do a disservice by training individuals to ignore potential dangers (e.g., gunfire in close proximity) that should prompt critical actions (i.e., tourniquet application and returning fire) and instead have them pack wounds, perform needle decompression, or conduct endotracheal intubation (skills that are not part of Care Under Fire. The response to a dangerous stimulus is extinguished, and development of effective situational awareness is hindered. This may be counterproductive in situations of real-world combat or imminent danger, where a keen sense of situational awareness is necessary for survival. This concept needs to be thoroughly understood and taught to instructors. Instructors need to know their students’ level of experience and adjust their training techniques appropriately.

When Adding Stress and Complexity Is Beneficial

Immunizing trainees to harsh and stressful environments in which imminent danger exists is certainly reasonable, although even advocates of these training techniques strongly recommend they be incorporated into a more comprehensive, measured framework—and only after core skill development has taken place. This follows the tried-and-true, stepwise crawl-walk-run approach to building strong fundamental skills.

SET is a comprehensive, multifaceted training model adapted in various forms by different military units, NASA, and other high-risk organizations to train individuals in domain specific skills and gradually expose them to increasing levels of stress. The goals of this training are to gain knowledge of and familiarity with a stressful environment, to develop and practice task-specific skills (including various psychological skills) as well as decision-making faculties to be performed under stress, and to build confidence in an individual’s capabilities. When properly adapted in different environments, the technique has demonstrated notable improvements in performance: improved examination scores, response time to perform technical skills, and accuracy of complex flight skills. Saunders et al conducted an extensive meta-analysis evaluating the data showing the various benefits of SET in various military and civilian domains. Originally proposed by Driskell and Johnston, SET takes a modified approach using three phases:

- Phase One: Information provision. This phase provides information on the human stress response, conditions participants on what they should expect to encounter, and other preparatory information.

- Phase Two: Skills acquisition. This phase is designed to develop and refine behavioral, technical, and cognitive skills.

- Phase Three: Application and practice. This phase includes practicing skills under conditions that approximate the operational environment and that gradually attain the level of stress expected.

In the first phase, preparatory information is provided to trainees. They are taught about the physiological response to stress normally and how these natural physiological mechanisms can interfere with the specific cognitive processes and technical skills during resuscitation. It ensures that everyone understands this deterioration is normal. Furthermore, it generates accurate predictions of how they will respond, which is critical to future success. By providing them with precise expectations, people perform better under stress. Behavioral scientists have noted that giving individuals preparatory information before engaging in stressful situations tends to render stressful tasks less novel, increases the predictability that one will experience stress, increases one’s sense of self-control, and decreases the tendency to misinterpret the stress response as catastrophic. Another important part of this phase is clarifying that providers are not helpless in the face of this hard- wired response. Crucial to success is the belief that people have the capacity to exert control over their behavior. This understanding of self-efficacy has been linked to improved performance in different domains. This understanding also allows one to predict potential areas of weakness and to motivate individuals to obtain the necessary skills to improve their

response under stress.

Perhaps the most time-intensive and most important part of the training paradigm is phase two. The goal of this phase is to develop the host of technical and nontechnical skills needed to perform effectively without the addition of stressful stimuli. The goal is to learn and develop constructive coping mechanisms and to build successful performance habits. The fundamental technical skills of emergency medical care must be established in conjunction with various cognitive and behavioral techniques.

In phase 3, application and practice are designed to rehearse the skills sufficiently developed in phase 2 under increasingly stressful conditions. This allows trainees to experience, in real-time simulation, the various performance challenges they will face in a specific setting (e.g., combat, active shooter). It also reduces uncertainty and anxiety as well as increases confidence when individuals realize that they can overcome stressors. Finally, stimuli experienced during stress training are less distracting when experienced in real life. Requisite to these desired effects is a graduated approach to stress exposure. It is by incrementally increasing the level of stress that the desirable outcomes (i.e., familiarity, resilience, and confidence) are developed.

Effective Teaching and Development of

Medical Skills for the Prehospital Trauma Setting

If the goal of TCCC, TECC, and STB training is to teach live-saving medical skills so that the trainee can reproduce these skills in the future on the battlefield or at the scene of an emergency (i.e., near and far transfer of skills), it is important to understand how the brain accomplishes these tasks. Understanding the process of information recognition, consolidation, storage, and recall can be framed within the concept of CLT. CLT was initially presented by Sweller et al in 1988. In CLT, there are three types of cognitive processing “loads” placed on the learner’s mind: intrinsic, germane, and extraneous. It is the sum of these three loads that describes the total amount of mental effort required by working memory, also referred to as the overall cognitive load of a task. The intrinsic load is the inherent mental workload (difficulty) imposed by the material or task. If elements or pieces of information need to be understood and employed simultaneously, then an activity is said to have high element interactivity, which increases the intrinsic load. Additionally, some concepts, in and of themselves, are inherently more difficult to understand than others. The intrinsic cognitive load is generally the most difficult to alter, but good coaching and teaching may have a mitigating effect. Direct guidance and feedback to novices working through skills for the first time avoids frustration, helps prevent errors, and enforces correct practice. This reduces intrinsic load as well as improving performance and the transfer of skills. Specifically, for a complex information-processing skill during a computer simulation game, direct guidance and feedback helped experimental subjects complete tasks faster and answer questions correctly more frequently than was the case without such guidance and feedback. For complex aviation tasks, such as landing a fighter jet on an aircraft carrier, direct guidance and feedback during aviation simulation resulted in fewer procedural errors and fewer deviations from the glideslope on approach to the carrier. In contrast, some traditional training philosophies that do not provide guidance and feedback, such as “training to failure,” “let them figure it out by making mistakes,” or “they have to fail to get it right,” are likely unhelpful when it comes to training novices (see extraneous load, below).

It is important to mention that learners should have the time to work through more complex situations and solve novel problems without guidance. However, this seems to be beneficial only with experienced learners who have consolidated foundational principles and have strong skills. These individuals benefit less from activities that guide them and that reduce the intrinsic load of the material because these persons have likely mastered them already. More experienced individuals can thrive with the introduction of challenges, nuance, and active forms of learning. Complicated scenarios that force this group of learners to actively engage, make and commit to decisions, and execute skills facilitate deep processing and improved retention of information.

The germane load represents the working-memory resources used to manage the intrinsic load. It can be thought of as the “brain power” used to make sense of information presented, incorporate it with information already known to the learner, and store it for future recall. In the parlance of cognitive science, this is referred to as the construction and automation of schemas. Because of working memory’s finite capacity, the brain uses schemas—structures that organize and relate many pieces of information into one unit—to increase efficiency of processing and enable automation. This is the theoretical explanation why complex, challenging, or stressful scenarios benefit experts but do not help novices. Experts experience notably less intrinsic cognitive load from tasks they have mastered; therefore, they can put substantially more mental resources toward the germane load for processing complicated situation-based exercises.

The third cognitive load, extraneous load, is irrelevant to the material’s substance. It detracts from learning and has a negative effect on skill transfer. The extraneous load is determined by how the information is explained or delivered. For example, if a concept is explained using confusing diagrams and with unnecessary information, the extraneous load increases. If the material is presented clearly, with little distracting information and in an easily understood manner, the extraneous load on a learner’s cognitive capacity is minimized. This adds to the argument of why adding stressors for novices is likely unhelpful. Gunfire, noise-flash, distraction devices, and screaming all probably add to the extraneous load for novices. Even seemingly innocuous distractions, such as interesting but only tangentially related anecdotes (e.g., war stories), might add to the extraneous load.

Some educational strategies seem to benefit virtually all groups, from novices to experts. First, activities that force learners to recall and apply information, such as practice tests, answering questions about material just learned, or even reciting material, have demonstrated effectiveness. It also may be beneficial for instructors to carefully customize training based on novices’ needs; if they are struggling, additional guidance and structure can be provided. If a learner breezes through the basics, further challenges may be provided. This adaptive technique may facilitate positive near and far transfer. Partial task training is a technique whereby a multi-step, often complex or high-risk technical skill (e.g., cricothyrotomy) is broken down into its individual competent steps for separate training and then combined so that the entire procedure can be performed. This technique may also reduce the intrinsic load of more complex skills. When a skill is broken down and practiced with variable emphasis or focus as part of a comprehensive sequence, a positive effect on transfer occurs. Also, the temporality of training is important. Spaced repetition over multiple sessions and increasing intervals between practice demonstrate better skills acquisition and retention.

An adage in the Special Operations community is, “Don’t train until you get it right. Train until you can’t get it wrong.” This statement has some truth to it. Initially, when learning a new skill, novices are simply trying to understand the task. Their experience revolves primarily around doing a task “correctly” and avoiding mistakes. Before long, mistakes become increasingly less common, task completion becomes smoother, and learners no longer need to expend significant mental resources focusing on the task. In fact, often fewer than 50 hours of practice are required for a number of simple motor skills and recreational activities before an “acceptable standard” of performance is achieved. However, the point at which learners feel things start to get easy and gross errors become rare is far from mastery. Although rates in error commission don’t noticeably change, task performance continues to improve over weeks, months, and years. In particular, there are two primary measurable changes as practice continues: the speed of task performance increases, and the attentional cognitive resources required to perform decrease. Some authors have referred to this as “overlearning.” The temptation is to stop when competence is achieved or even when an individual can complete error-free task performance. Incremental improvements persist beyond this point, and the salient “I feel like I got this . . .” is not a good marker to terminate learning, especially when it comes to high-risk emergency procedures.

A concept that encapsulates these various aspects of effective training is that of deliberate practice, proposed by Ericsson et al. Deliberate practice is a very specific, effortful type of practice defined by several practices (Table 1).

TABLE 1 – Deliberate Practice Concepts

| Develops skills that other people have already figured out how to do and for which effective training techniques have been established |

| Involves well-defined, specific goals and often involves improving some aspect of the target performance |

| Takes place outside one’s comfort zone and requires a student to constantly try things that are just beyond his or her current abilities |

| Occurs regularly and extends longitudinally |

| Involves building or modifying previously acquired skills by focusing on particular aspects of those skills and working to improve |

| Involves quantitative and qualitative feedback and modification of efforts in response to that feedback |

| Produces and depends on comprehensive mental representations of the target task |

| Is deliberate, which is to say that it requires one’s full attention and conscious effort |

Adapted from Ericsson KA, Pool R. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2016.

This deep, intense, and deliberate practice can be enjoyable and even personally all-consuming, but it can also be challenging and frustrating. A trainee who completes a scenario and states, “That was awesome!” or “That was a crazy scenario!” has not necessarily walked away with skills or knowledge. This is not to say that training shouldn’t be engaging, but rather that attention should be paid to ensure it includes fundamental evidenced-based teaching techniques and also is entertaining. Training that is fun or easy does not necessarily equate to effective training. This concept is known as training-transfer dissociation. Several variables in training that make it easier or more entertaining don’t necessarily facilitate transfer of skill and information. Many learners often make this assumption and conflate ease and enjoyment with quality and effectiveness. The instructor should be aware of how students may interpret scenarios in regard to efficacy and learning.

The Role of the Prehospital Medical Instructor

The instruction, guidance, coaching, and feedback provided by seasoned, experienced instructors and teachers are paramount to successful learning. Such instruction begins with understanding students’ capabilities and limitations. Evidence suggests that there is a direct impact on education when instructors

understand the knowledge and beliefs that learners bring to the encounter. Instructors should understand the level of experience of trainees, their individual frames of reference when it comes to key concepts and skills regarding tactical medicine, and how these frames of reference have come to be. Do the students have a significant amount of medical experience treating patients in the prehospital trauma setting? Have they learned habits from previous courses or their own experiences that may not be in accordance with best practice for the course? Such awareness can drive effective, adaptive, and timely training that best meets the needs of the students.

Aside from developing curricula and using evidence-based techniques, perhaps the most important role of an instructor is to provide feedback. Feedback has been well studied and is integral to both deliberate practice and learning across disciplines. The timing of feedback and direction is vital. Authors have examined feedback during task execution (i.e., concurrently), immediately after a skill is performed (i.e., adjacent feedback), and minutes to days after an event (i.e., delayed feedback). When students are interrupted and given concurrent feedback, they may not process the feedback particularly well. Cognitive scientists suggest that this is called dual-task interference: their brains are so busy processing information and trying to execute a skill that the feedback isn’t processed or incorporated. Likewise, if feedback is done hours or days later, the information may lack temporal contiguity: the learners don’t recall the events or what they did and therefore cannot incorporate the feedback appropriately. Feedback immediately after task performance may be the most effective. When it comes to coaching discrete medical performance skills, the content of the feedback and what instructors tell students is particularly important. Referring back to the understanding of cognitive load, feedback should generally aim at decreasing intrinsic load, optimizing germane load, and eliminating extraneous load. Retrospective research into effective coaching and skill development seems to echo this sentiment. Feedback by master coaches is timely, succinct, specific, and action-focused. It is also generally iterative: the skills are repeated and evaluated to see whether feedback was incorporated appropriately, followed by confirmation or further clarification. Other novel methods for providing immediate timely feedback in conjunction with quickly repeated practice have demonstrated benefit.

A recent study demonstrated that rapid cycle deliberate practice (RCDP) was superior to post-simulation debriefing (PSD). RCDP used direct and timely feedback from the instructor to the user. Traditionally, a PSD model is used in training for pre-hospital medicine on the battlefield, which consists of a team-based simulation followed by a long, after-action review, otherwise known as a PSD. RCDP differs from this strategy by providing a known script and choreography between the team members while the instructor provides real- time feedback through coaching and inquiry. Simply, there should be no secrets as to how to treat common scenarios and what exactly should happen on the individual and team levels during these actions. Using this approach has been shown to increase confidence and reduce cognitive load while being conducive to long-term retention. Ultimately, it aims to reduce time between scenarios by eliminating long debriefings so that more quality repetitions can be achieved in a shorter period.

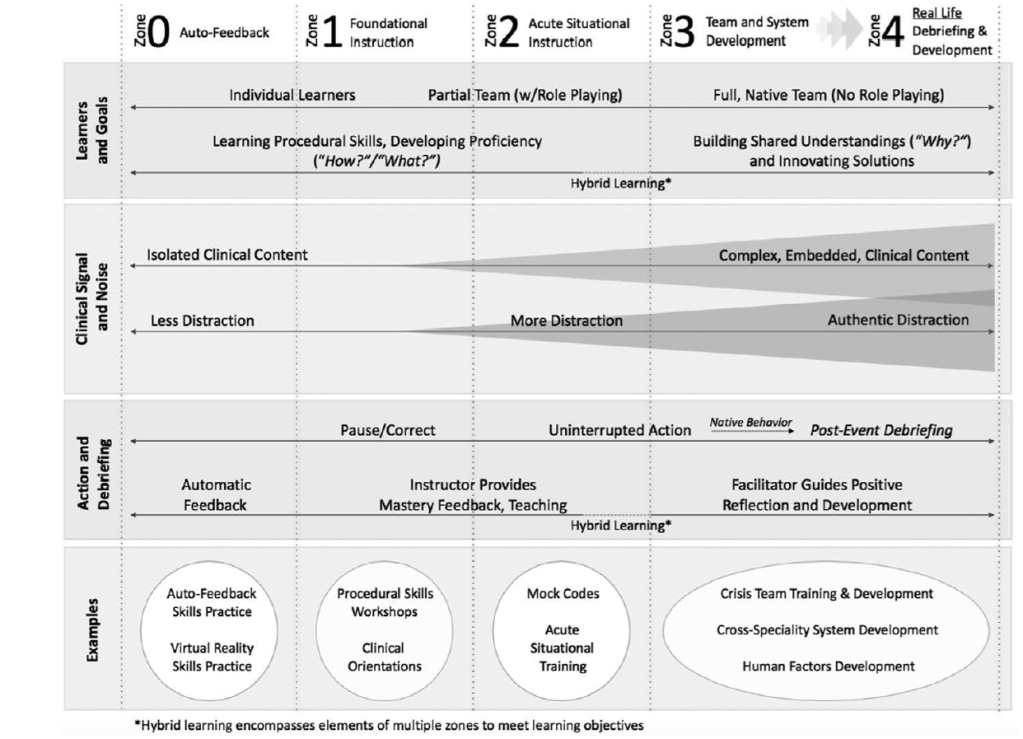

Regardless of the strategy used, the cornerstone of high-quality instruction is demonstrations across all facets and training modalities led by subject matter experts. Often, demonstrations cease to happen after the individual skills stations or the Zone 0 period of instruction (Figure 1). In turn, a gap is formed between doing the specific skills and then actually putting them all together in a realistic scenario. This gap is often too large a steppingstone for students to bridge on their own accord and is easily mitigated through full-assessment demonstrations by subject matter experts. It is important that students continue through every zone of instruction until they are in Zones 3 and 4. Additionally, regardless of student competency or experience, refresher courses should be reset back to Zone 0 or Zone 1 to build back up from that point to prevent basic skill atrophy. Similarly, if an operational unit is not performing well during team-based scenarios (e.g., Zone 4), then the scenario should be scaled back as necessary. If possible, the team should be reset back to Zone 2, where RCDP can be performed until mastery is achieved before introducing the element back into overly stressful situations that are producing subpar results and creating bad habits.

FIGURE 1 SimZones framework that guides all course development and delivery at the Boston Children’s Hospital Simulator Program, 2015–present.

From Roussin CJ, Weinstock P. SimZones: an organizational innovation for simulation programs and centers. Acad Med. 2017;92(8): 1114–1120. Used with permission.

Conclusion

Understanding the elements of instruction that produce highly trained and efficient performers should be the goal of every instructor, teacher, leader, mentor, and professor. Over time, our understanding of cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and education has evolved. It is important that instructors understand and incorporate these concepts in prehospital trauma training. Past achievements and experiences are meant to facilitate growth, strengthen one’s resolve, and ultimately help instructors develop into well-rounded individuals. Instructors cannot stand on virtue and past experiences alone; they must amend their techniques to include the science of effective teaching and training. In light of developments in the science of technical skills development, far skills transfer, and deliberate practice, certain training techniques should be reconsidered. Furthermore, modalities should be updated to include the fundamental principles of such concepts as deliberate practice, CLT, and SET.

- Jonathan McCarthy is the Operational Medicine Program Manager for SIMMEC Training Solutions, an extramural training provider that specializes in the use of Advanced Medical Training (AMT) models for the DoD and other relevant entities.

- Dr Michael Lauria is affiliated with the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM.

- Major Andrew D. Fisher is affiliated with the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, and with the Texas National Guard, Austin, TX.

Correspondence to Jon@simmectraining.com and/or anfisher@salud.unm.edu

Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures to report.