Purpose: The intent of this article is to consider how a military medic can address traumatic brain injuries using just an aid bag. The target demographic is a Tier 3 Combat Medic/Corpsman or Tier 4 Combat Paramedic, Special Operations Combat Medic or above. This is also for their senior medic / provider using this as a resource to guide training, through discussion or a physical TCCC trauma lane. Tier 3 medics may consider adding tier 4 skills and procedures when appropriate, if trained, proficient and current, approved through a unit provider.

Scenario: You are a medic assigned to a line infantry Company. Your Platoon is tasked with clearing hostile structures in the area. During clearing operations you are set up in a pre-established CCP. In the same building as your CCP, you see 1st Squad preparing to clear a room at the end of the hallway. After the point man enters the room, you hear an explosion and see dust pour out of the room before the rest of the Squad can get into the room. They push into the room and a minute later you see a casualty being dragged towards you. 1st Squad’s CLS reports to you with a minimally responsive soldier covered in dust as you begin your assessment.

M: Pt has a TQ applied high and tight to the right leg with a blood soaked pant leg. A laceration is noted to the distal/medial thigh with controlled bleeding.

A: After coughing up some dust, Pt appears to be moving air adequately.

R: Pt is breathing with an adequate depth at a rate of 18.

C: Pt has a present radial pulse at 110 bpm and delayed capillary refill. Pt has scattered scrapes and cuts with minimal bleeding across his body.

H (Head): Pt is noted to have some bleeding from his ears and is minimally responsive to painful stimuli. Pt will withdraw from pain and groan upon a firm trap pinch, but does not open his eyes. Pupils are equal but sluggish upon assessment.

H: (Hypothermia): Pt is wrapped in a trauma blanket after initial assessment.

What are your initial concerns? How long can you sit on this patient? What is your treatment plan?

(Now is a good time to stop and discuss as a team.)

Life threats always take priority in medical care and TCCC holds no exception. When dealing with conditions such as head injuries, eviscerations, and others for training and actual patient care, we must ensure we address life threats first and don’t allow more visually disturbing injuries to distract us. The assessments within Massive hemorrhage reveal bleeds already controlled; Airway doesn’t appear to be an immediate issue right now; and Circulation reveals some concerning findings.

When training TCCC, ensure the MARCH tool is applied and followed in order.

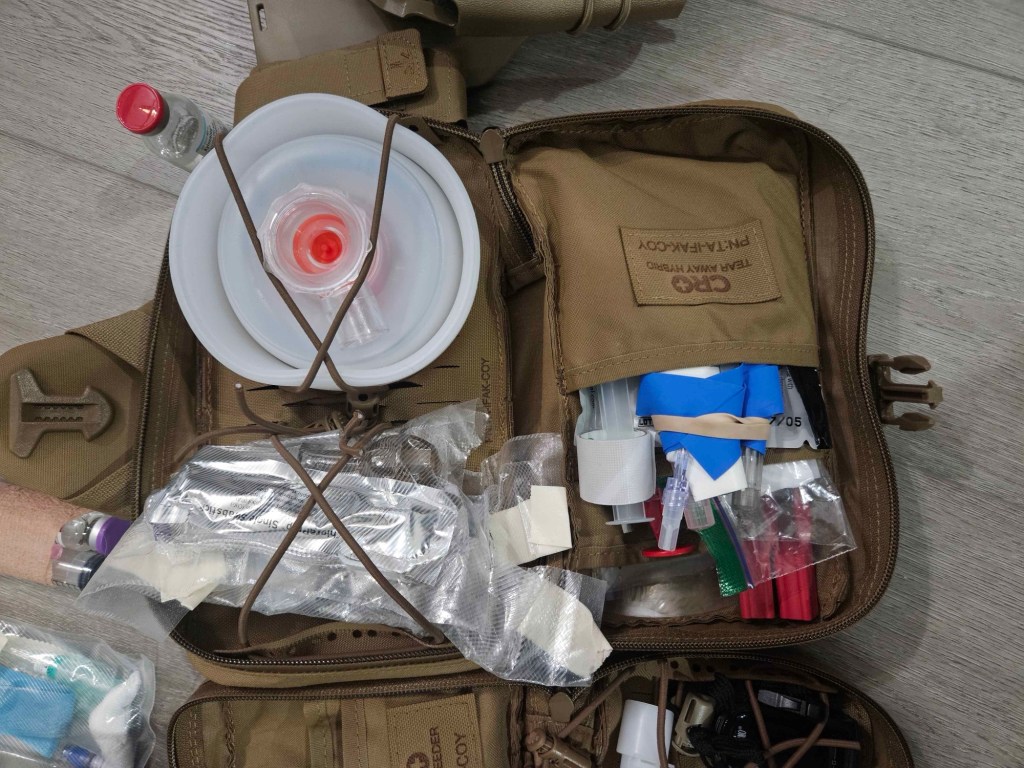

Every medic’s aid bag differs based on the unit type, medical logistics, level of training, certification, and medical direction relationship. In this article, we’ll discuss several treatment options that hopefully will be feasible from your aid bag. We are unable to carry everything, all the time, for everyone–but we can expect a medic to make decisions on what to carry in order to do the best they can with what they have. Knowing the limitations of the individual medic’s with their aid bag is critical to understand the tiering of medical infrastructure from role 1a (the medic) through role 1b (truck), role 1c (aid station), and beyond.

Firstly, treatment of any TBI starts with one main concept: maintaining cerebral perfusion. We can do this in several ways; here are three known mortality multipliers that must be prevented at all costs.

- Hypoxia – SPO2 below 90%

- Hypotension – systolic blood pressure (SBP) below 90 mmhg

- Hypocapnia/hypercapnia – End Tidal CO2 (ETCO2/capnography) below 35 mmHg or above 45 mmHg

In simple terms, Hypoxia is the brain not getting enough oxygen, Hypotension means there is not enough pressure to carry the oxygenated blood to the tissues, and Hypo-/ercapnia means the quality of the blood arriving in the brain carries too little or too much CO2. Any instance of these items alone can lead to over double the mortality (odds of dying), and when two or more of these events occur then mortality can skyrocket. However, there are several steps we can take to prevent these adverse events.

You may have heard of hyperventilation and have probably even seen it in the TCCC guidelines. This is a tool we will discuss later, but for now, remember that prolonged hyper- or hypocapnia is deadly. If hyperventilation is considered, it should only be done so in the presence of capnography (EMMA device). More on this later in the article. Let’s go back to our injured soldier to discuss our options.

Do these concerns change your treatment plan?

After your initial assessment of the patient, you proceed to some further evaluation of vital signs. You place a portable SPO2 on the patient, take a manual blood pressure, and re-assess your patient’s respiratory effort.

Pulse: 112, weak

SPO2: 94%

Blood pressure: 94/60

Respiratory rate: 18

Airway: Sonorous respirations.

(If you are discussing this as a team, now is a good time to pause and discuss what these mean for us, what could raise our suspicions or clue us into additional treatments)

You sit the patient up onto a rucksack against the wall to keep their head at roughly 30 to 45 degrees. This position helps them maintain their airway. This change in positioning relieves their sonorous respirations and their SPO2 increases after a couple minutes. You consider a nasopharyngeal airway in case the positioning change does not keep the airway open.

You gain IV access after recognizing this patient likely needs resuscitation with blood. You activate the walking blood bank and begin the process of filling a blood bag. You administer a slow push of two grams of TXA while waiting for the bag to fill. Once you have a unit of whole blood ready you promptly administer it… but what blood pressure are you aiming for?

Resuscitation in the presence of severe TBI

Damage control resuscitation guidelines tell us to titrate to a SBP of less than 100 mmhg. Permissive hypotension may be a consideration in the bleeding trauma patient, but if we do this in our TBI patients, we may sacrifice the brain to save other organs. In order to protect and perfuse the brain, we need to aim for a higher SBP. The JTS recommends aiming for a SBP of greater than 110 mmhg.

But, why?

Normally, the TBI patient may begin to become hypertensive to compensate for the increase in intracranial pressure (ICP), in order to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). The brain, unlike the periphery, does not like large swings in perfusion pressure. It uses hypertension to increase the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and autoregulate these changes and keep them small. This is seen in this simple formula: CPP=MAP-ICP. This formula illustrates that as ICP increases our MAP must increase to maintain our CPP.

(For a deeper understanding of this formula click here).

In the presence of a TBI and blood loss, the body may not be able to muster an increase in blood pressure going into the skull to protect the injured brain. This is where we need to compensate with our resuscitation efforts. Low-titer O negative whole blood is preferred, but if unavailable, component therapy can be utilized. The JTS also recommends the aforementioned two grams of TXA to be administered as soon as available. TXA has been shown to reduce mortality in the TBI patient, and improve their neurologic recovery over the next six months.

Training Consideration: Including head injury patients in training means being aware of blood pressure ranges outside of a standard trauma patient without head injury. If a medic only has non-head injuries memorized or considered, then they may see a 94/60 as adequate, or an 88/58 as not as concerning as it would be in a patient with a TBI.

What is your next priority for this patient?

Your patient is beginning to turn the corner thanks to you focusing on giving blood. His skin is pinking up, blood pressure has increased to 112/78, and his pulse rate has come down to 84 bpm. You have already passed up a 9-line and MIST report but you are waiting for ground evac, and the ETA is approximately six hours. You have triaged this patient as an urgent casualty, but no air assets are available. We now need to think about the possible complications that may occur during that time.

The skull is an enclosed space housing 3 main things: The brain, blood, and cerebral-spinal fluid (CSF). When one of these items increases the others should decrease, but in our TBI patients we may have an increase in blood (due to bleeding) or swelling of brain tissue that cannot be compensated for. When this happens our intracranial pressure increases and the items in our skull have nowhere to go.

As intracranial pressure increases, we need to be on the lookout for signs of herniation. Herniation is when the pressure in the skull gets high enough that parts of the brain push into the other structures in the skull, causing abnormal neurologic function. There are many types of herniation. It is not important to memorize all kinds of herniation, but it is important to know that they may present differently depending on the location. This movement of structures can cut off blood or cause damage to vital parts of the brainstem that control breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. Frequent neurologic assessments and vital signs trends are important to catch these changes early.

(To learn more about herniation click here).

Neurologic changes to be assessing for:

Unilateral Blown/non-reactive pupils – brains changes are impacting eyes

Loss of gag, cough, or swallow reflex – airway is at risk since it can’t protect itself

Changes in LOC.

Posturing (sign of herniation and brain death).

Any decrease in GCS scoring or worsening neuro exams. (see here for GCS and here for T-MACE (short MACE for aid bag), and MACE2.)

Training Considerations: Do we expect a medic to have a T-MACE or MACE2 memorized? No, but even if they carried a physical copy, they should have red flags memorized so they can always look for and ask about those in any suspected TBI in garrison or deployed. There is also a TBI navigator app that walks a medic through it with their phone/device in a situation where that is appropriate.)

Airway concerns:

– Loss of gag, cough, or swallow reflex (airway patency and protection).

– Nausea/vomiting (aspiration risk).

Seizures

Vital sign changes:

Abnormal changes to respiratory rate and effort or development of irregular respiratory pattern.

Bradycardia (sign of neurogenic shock).

Hypertension with or without widening pulse pressure. (Systolic and Diastolic get farther apart.)

In the presence of impending herniation medics should reach for a couple items. 👇🏻

Non-pharmacological ways to decrease ICP:

- Keeping the patient’s head at 30-45 degrees will help the drainage of blood and CSF out of the skull and decrease ICP. This is simple, but you may see it often missed in TCCC as medics chase pushing Hypertonic Saline.

- If cervical collars are utilized, it is important they are loose. Cervical collars can increase ICP by up to 3-5 mmhg if they are too tight.

- Hyperventilation with a BVM may be considered to decrease ICP in short durations (20 minutes). However, Hyperventilation means either having a second person hold the mask on the face, or getting an airway such as a cric. Hyperventilation is an advanced skill and should be trained on and utilized only in the presence of ETCO2 monitoring ( using EMMA capnograph), and after training by a provider otherwise we could bag for our patient too little, or too much. If utilized, TCCC guidelines state to aim for a ETCO2 of 32-38 for short durations, although JTS CPG’s state 35-45. This should be reserved as a last ditch effort and discussed with unit provider. The question isn’t as much whether or not to hyperventilate but how little it does for the patient, if anything. Focus on other wins in the guidelines.

Hypertonic Saline (HTS):

- Hypertonic saline has a higher concentration of sodium chloride compared to normal saline (3%+ vs 0.9%). This solution pulls fluid out of tissues and into the blood vessels. In the setting of TBI, HTS pulls fluid out of brain tissue and causes a decrease in tissue swelling. This helps decrease intracranial pressure.

- Without invasive ICP monitoring, we cannot accurately measure the effects of HTS. HTS should be given and the casualty should be immediately evacuated. Only in extreme situations should we sit on a patient needing HTS.

- A 250 or 500 ml bag of HTS can be carried in an aidbag, but it takes up significant space and could be confused with a bag of clear fluid, risking a patient getting HTS that didn’t need it. HTS also comes in a 23.4% concentration in a 30ml vial. Vials of HTS 23.4% can be carried and given via slow IV push over 10 minutes (as per TCCC TBI guidelines) or diluted in a bag of NS (0.9%) to be administered via bolus. Carrying 23.4% HTS can save space as well as decrease the chances of medication errors. If bags are used or HTS diluted, red tape or labels should be used to differentiate between standard clear fluid bags.

- Sodium Bicarbonate may also be considered as a surrogate for HTS as it sits at 8.4% and is a hypertonic solution. 2 amps may be placed in a 250 ml bag of NS. Clearance through medical direction should be discussed before using this option.

Sedation and pain management:

- Despite having a decreased LOC, TBI patients still experience pain. Agitation and pain may cause increased levels of ICP.

- Ketamine and Fentanyl are both appropriate options for treatment of pain.

- Midazolam 1-2 mg IV/IO may be considered for anxiety and agitation. Benzodiazepines have long durations and their impacts may need to be considered during neuro exams.

Airway management:

- TBI patients may not be able to manage their own airway due to herniation, vomiting, or seizure activity. A medic should be weary of a patient getting worse and needing an airway.

- Manual BVM ventilation may be effective, but requires the medic to be continually maintaining good mask seal and airway maneuvers. Ensure a medic always carries a PEEP valve with their BVM.

- Any addition of positive pressure ventilation (PPV) with a BVM can decrease a patient’s blood pressure. PPV can also risk a tension pneumothorax, which means dealing with that on top of our head injury patient. We’re not saying not to ventilate, but medics need to understand the risks of all interventions they perform.

- Special care should be taken to ensure no hypoxic events occur during the placement of any airway device by appropriately oxygenating prior to any event and keeping advanced airway attempts as brief as possible.

- Surgical cricothyroidotomy is recommended in the TCCC environment. Without doing an entire airway lecture, it’s the airway Tier 3 medics are most familiar with, it doesn’t require advanced medication that is risky in tactical scenarios (sedation +/- paralyzation), and can even be done with or without topical anesthetics, like lidocaine.

- Endotracheal intubation (ETI) or supraglottic airway (SGA) may be indicated for Tier 4, or 68W Tier 3 who are well trained, experienced, and have performed these recently enough to be good at them. These devices often require large amounts of continual sedation that may not be available and a patient should not be intubated if such cannot be sustained. It is also important to consider that intubation itself may increase ICP.

- BVM Training Consideration: Whenever the BVM comes out, an Instructor needs to do intermittent quality checks. It’s common to have a weak grip and let air flow out sides if doing a face-mask seal, especially with C & E grip instead of Two Thumbs Down. Some may use straps to go hands free, although this may also cause air leaks. An NPA or two may assist with bagging with a face mask seal. Laterally rotating the head to the side may also help with compliance.

It’s also common for a medic or non-medic handling BVM to squeeze way too much volume of air into the bag, which can damage lungs and decrease cardiac output. They can also get distracted with watching other interventions and forget to squeeze the bag for long periods of time, or get amped up at what is going on and hyperventilate every second or two. Consider enforcing a rule that personnel using a bag-valve mask count out quietly, and make on the spot corrections immediately so poor muscle memory doesn’t get formed. Consider unit level training on this skill itself before TCCC lanes, and validated during TCCC/PFC.

Treatment of seizures:

- Pt’s who are herniating may begin to have seizure activity. Along with HTS, typical means of seizure control can be attempted. Benzodiazepines may or may not be effective, and larger than normal doses may be needed. The JTS recommends the following:

- 5mg midazolam Q5 IV/IO/IM until seizure activity stops. This is the most likely available seizure medication a combat medic has available. Midazolam can be given intramuscular if IV access isn’t available yet, or patient’s seizure is interfering with access to an IV in the antecubital fossa due to bent arms.

- 5 mg diazepam Q5 IV until seizure activity stops, (Rare in aid bag, more likely Role 1), or

- 4mg of lorazepam Q5 IV until seizure activity stops. (Also a more Role 1 medication)

- Advanced airway management should be considered in the seizing TBI patient.

- Prophylaxis: Most medics do not carry seizure prophylaxis, but depending on supply chain, medications like Keppra may be available and could be considered if feasible, especially if mounted, or at a Role 1 or above. Discussions with medical direction should be had about dosage if other narrow therapeutic medications are considered, such as Phenytoin.

- Refractory seizures: Without getting advanced, you may encounter seizure patients that don’t respond to multiple doses of benzodiazepines. This may mean considering Ketamine and/or Keppra. Not trying to expand the deeper rabbit hole, but a consideration for a medic to discuss with your provider in training. For now, memorize seizure treatment name, dose, onset and frequency of redose.

- Other means of decreasing ICP should be utilized as feasible to assist with seizure cessation/prevention.

- Seizure training considerations: A new medic may not be aware of managing a seizure. A novice medic may not know the dose. An emergency is not the time to be looking up something, so there are some medications and doses a medic should have memorized. I consider this a medical “tap rack bang”, or troubleshooting we should know. At minimum, a quick reference sheet to double check dose to prevent error. Even an experienced medic may rely too much on one 5mg dose on Versed, which may break some seizures but not other ones. You can consider incorporating seizure patients in training that need 2-3+ doses before siezure relents so a medic is prepared not only for first intervention, but also follow up doses if that doesn’t work.

Treatment of vomiting:

- Antiemetics are recommended in the case of TBI due to potential for airway contamination by vomiting, which can come up and get into the trachea (aspiration). 4mg – 8mg of ondansetron is frequently carried by combat medics and can be utilized prophylactically.

- Ondansetron has shown some mortality benefit in TBI patients.

- Consider alcohol wipe as a stopgap while zofran or other medications are being drawn.

- If available, escalation to medications like Promethazine, Reglan, droperidol or Compazine at the risk of increased sedation or cardiac side effects depending on the medication.

Fever control:

- Acetaminophen 650 mg PO Q4 along with active and passive cooling measures are recommended for temperatures over 99.5 degrees F.

- Some guidelines used to recommend temperatures outside normal. That is no longer the case.

Triage and Transport considerations:

- A medic should understand that all the above treatment methods are temporary. The severe TBI patient requires urgent neurosurgery.

- Patients with severe TBI should be considered urgent and be evacuated as soon as possible.

- Evacuation locations should have imaging and surgical capabilities.

- Depending on the tactical situation, patients with severe TBI and respiratory effort should be triaged red/urgent.

- If TBI patients are apneic despite advanced airway placement, then prognosis is poor. These may be triaged grey/expectant depending on the tactical environment.

What complications would you be able to treat out of your aid bag?

4 hours later, your injured Soldier begins to show signs of herniation. He is bradycardic at 46 bpm, has a BP of 150/100, and has begun breathing erratically with varying depths. You administer a 30ml 23.4% HTS bolus, 4mg of zofran if not already done, and prepare equipment for airway management. The patient’s breathing normalizes, but he does not have any airway reflexes. You opt to perform a deliberate surgical cricothyroidotomy and coach your CLS with BVM ventilations. You utilize an EMMA device on your BVM to target a normal ETCO2 (35-45 mmhg). You use ketamine for pain management until ground medevac arrives. You consider sedation and make a plan to use a larger dose of ketamine with fentanyl pushes if needed. You handover care without any additional complications and the patient is transported to a facility with neurosurgery capabilities. You return to your platoon and mentally prepare for your next casualty.

Additional training considerations:

If you’re looking to run this as a physical lane, or talk through it for training, here are additional considerations for your team to discuss with senior medic and providers:

- What if the patient did not respond to blood products? (Discussion on expectant care and utilizing resources available, especially if you have multiple patients who need blood.)

- If this was from a vehicle rollover and the patient had a severe TBI and internal bleeding from a pelvic fracture, how does this change things? Does this mean resuscitation to 110mmhg or only 90mmhg? This is an advanced juggle that providers can talk you through and you can find suggestions for in guidelines and CPGs.

- What if this was a less severe TBI, such as a concussion? Some tend to refrain from using the term mild TBI or mTBI because “mild brain injury” can underestimate how bad this can be, which certainly isn’t mild. In addition to knowing TCCC guidelines for a severe TBI, I recommend every medic/corpsman be intimately familiar with the T-MACE or MACE2 exam. It’s not perfect, but it’s a good minimum foundation for a medic to know. While I do not expect a medic to memorize the entire T-MACE/MACE2, the red flags on the first page should be memorized and assessed in every single (potential) head injury. This is a good hip pocket class to teach your medics, something you should expect them to be able to recite, and brief you on every time they had a potential concussion patient in training.

- What if the T-MACE, MACE2, or TBI Navigator app was positive for a mild concussion and you returned from a patrol with your TBI patient who only had mild symptoms? Use the Return to duty guidelines and your provider to discuss getting them back into duty, operational constraints allowing. You also want to ensure they don’t have the opportunity to get a second concussion within a short time frame, which can be difficult if the service member is the only one with their specialty on missions and can not be replaced.

I also don’t expect a medic to memorize this. However, you can know where it is, have easy access and understand some of the basic principles for knowing how to get someone from concussion symptoms to back in the fight.

Do you have any other treatments or considerations you would add?

Comment below.

If you want to dive deep on head injuries for training, classes and operations, here are references to discuss with your provider:

Traumatic_Brain_Injury_PFC_06_Dec_2017_ID63_Rapid_Update

TBI Management and Basic Neurosurgery in the Deployed Environment, 15 Sep 2023

Damage Control Resuscitation, 29 Aug 2023

Prehospital Blood Transfusion, 04 Aug 2020

Prolonged Casualty Care Guidelines

Neurologic injury and mechanical ventilation – PubMed

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/2810001

Hyperventilation in Adult TBI Patients: How to Approach It? – PMC

EPIC Guidelines for Prehospital TBI Management | North American Rescue

Brain Herniation • LITFL • CCC Neurology

Calculating Cerebral Perfusion Pressure | NursingCenter

Co-authors:

Emily M., 68W, NRP

Ricky Ditzel, BSHS, FPC, ATP

Collin 68WW1, PA-S

Next article could be YOU! Reach out to us.

🧠🧠🧠