You scroll through social media and see a study posted by a coworker or family member, “Vitamin X mixed with Tofu cures Cancer” (but if you look closer the study was on 6 mice.)

A coworker reposts an article “Chest seals must be vented unvented vented unvented vented” (but if you look closer the study is an opinion of a group)

Another medic shows you a study, “This brand new tourniquet always works” (but if you look closer it was tested on pressure sensing plastic manikins, not actual human legs under doppler ultrasound)

It’s really easy to lightly read a study’s headline, scroll down to the conclusion, then treat it as complete truth because we want to believe it. We have a responsibility to be skeptical, even when it’s something we would like to be true.

This guide is an introduction to help you sift out some of the weaker information so you can begin to evaluate them at a beginner level. Most medics don’t get formal education, but if you google other resources they can be provider oriented and difficult to digest. For the purpose of length this is not a comprehensive guide as that would be a whole book. Hopefully next time you see a study, you aren’t as gullible into believing a hot new trend, or that what you have been doing is completely wrong. (Although, that happens, too.)

If you are already a stud at reading studies, we hope this article makes it easier for you to share with your junior medics that send you studies that this article could easily screen. Let us know what you think we could add in email or social media.

Remember to check your study for T.R.A.P.S.!

To summarize the following article in a sentence, we need to check how many people are in the study, how they conducted it, it’s quality and how relevant it is to us.

First off, we wanted to make an acronym you could remember, or easily come back to work through.

- Type of patients

- Relevance to your field

- Amount of patients and data

- Pyramid of studies

- Second Opinion

TRAPS 🪤

Type of patient:

Type of patient deserves special attention. It is pivotal for your understanding of a study to be aware of the patients that are included. This is especially important for medication trial studies; where combination therapy (multiple of the same or similar class of medications being administered for the same goal) is common. Your “control” group may already be receiving medication, if you’re unaware you may attribute outcomes to lack of treatment (your usual control group setup) when in fact it was the initial medication that did the work, not a placebo. This is also true for understanding confounding variables: if all of your patients in a new opioid reversal trial were tagged as polypharm overdoses, you may not get the outcome you’d expect due to this patient selection. So think if the patient and what is impacting them could skew the results.

For Military providers, the healthy 18-40 year old men and women in service are of course not the same as many civilian studies with comorbidities and illnesses that include 50-70+ year olds, pediatrics and more. Something to keep in mind. It may mean the study may not accurately show how the demographic in TCCC may respond.

TRAPS

Relevance to patients, question/inquiry : Take our made up example at the beginning, “Vitamin X mixed with tofu cures cancer” or any other outrageous claim you’ve heard lately. If you look a little closer, they may be done on animals. While there is hope and potential in a study done on things other than actual humans, such as animals, mannequins or measuring devices, it doesn’t mean that is always how it works with all living human bodies, only that, “this is how it MIGHT work.” So you might want to add a study like this to the mental category of, “Interesting, I would like to see more data closer to human accuracy.” Animal studies can be a promising first step to lay groundwork for additional studies later on, however if you don’t notice it is on animals then a studies title of “This intervention saves lives” may seem misleading.

This is also true of studies outside of combat medicine being applied to TCCC, as mentioned above. A study on pelvic fractures from car crashes or falls with elderly patients may be different from studies showing 20 year old males stepping on mines, with shrapnel and dirt in the wound. So when looking at the demographic of a study, consider if the patients and mechanisms are worse or better than your demographic, or different. If they are giving medication to a patient with a small cut on their toe and they survive, it might not be as applicable to traumatic amputations. A study on civilian EMS ambulances or ERs may not accurately reflect combat injuries, treatments and survival. A study of paramedics treating thousands of 9mm and 556 gunshot wounds isn’t necessarily the same as Combat Medics dealing with IEDs, RPG’s, 50 Caliber and other catastrophic, dirty war wounds.

Lastly, we need to take provider level into account. If a study says that there is an 95% success rate of a procedure and therefore medics should do it… it might help to notice that a Paramedic or Doctor seeing dozens of patients a month will probably do better than a 19 year old 68W might. This can also be applied to the scenario of outcomes, as civilian hospitals may have equipment and capabilities that certain military scenarios might have farther away. Unfortunately it can be hard to get military relevant data if not tracked well, which may mean little to no data in certain areas. An example is tourniquets for closed femur fractures, because so many focus on traction splints since an ambulance can easily carry one. A dismounted Combat Medic or Corpsman with 50lbs on their back is not going to add 5-10lbs for a legitimate traction splint since that is a one trick pony not worth the weight, so they have to consider patient management without an ambulance.

TRAPS

Amount of patients and data:

There isn’t a golden number of how many participants should be in a study for it to be valid, but there is big difference between a study of 10 people, 10 animals, 100 people and a study of thousands or more. It’s about statistics.

For instance, if you did a study on two people and one lost their arm from a medication, it would be easy to say there is a 50% chance, when in reality it may happen 1 in every 1:1,000,000 if you studied a larger group. Statistics are more accurate in larger pools if done well. This is why anecdotal medicine is dangerous because one medic’s reality is “this side effect happens often” because of their luck and another medics reality can be “This never happens.” If you zoom out to see 10,000+ patients you will accurately see how often and severe the medications impact is more than just examples from one provider or region.

“The study I am looking at has a tons of people, so it’s great?” They also depend on the group it came from, even if a relatively large group. If you are looking at a study that has a lot of people, try to see what group it biases, or how different demographics could potentially not be represented or accurate. Wealthy patients or ones from certain demographics may represent differently for ways that aren’t obvious to the study. Numbers aren’t everything, as method matters, but they help.

There are specific terms to understand in order to speak the language of medical studies. This is a lot to take in, so if you don’t understand something on first read, then come back to it later so you can understand the whole process. You can always look up what a value means as you are reading a study in the future.

Null hypothesis: It means the treatment, medicine, or thing they are testing doesn’t make a difference compared to normal. If the study shows strong proof against the null, it means what is being tested probably works.

P value: A p-value shows how likely the results happened by random chance, with smaller numbers meaning stronger proof. This shows you if the intervention may actually be helping, or if it is just luck and patients are changing on their own unrelated to the intervention.

P values are made by those making the study, therefore they are not immune to accidental or intentional bias by changing what is included. Without a lengthy explanation, the big takeaway is that they help you, but they aren’t immune to being skewed.

Confidence Interval (CI): A confidence interval tells us the range where the result probably lies. Think of it as a safety zone around your number—like the odds ratio (explained next)—showing how precise your result is. A narrow CI means we are more confident in the estimate. If a 95% CI for an odds ratio doesn’t cross 1.0, that usually supports what the p-value is saying: that the result is statistically significant. Think of a confidence interval like a blast radius around a thrown grenade—it shows the likely zone where the real impact landed, and if that zone misses “1.0,” your result was likely a direct hit.

How is confidence interval applicable?

Lets say a study showed we treated these patients with a blood pressure(BP) medication, lisinopril, for their high BP.

After treatment maybe their pressure was 120 an average.

The “population parameter” if we were to repeat this study would probably have some variation if we repeated it 100 times. That’s OK. We can’t actually be 100% certain about anything. We don’t actually repeat the study 100 times

Let’s say we’re 95% sure that the truth would likely be between 115 and 123.

This would be expressed as 95% CI: 115-123). This means we’re 95% sure that the true population (the truth) is between those two numbers.

OR (Odds ratio) : An odds ratio shows how much more or less likely something is to happen with a treatment compared to without it. (Citation)

Mortality: This is how many people died during or after the study. This is incredibly relevant because in many discussions we’ve had lately we have noticed providers focusing on changing a patient’s lab values without understanding impacts on mortality. You could push a medication to fix a patients blood pressure, electrolyte issue or more but that does not mean it saves more patients than the provider that doesn’t fix those values. Changing a patient’s numbers doesn’t necessarily increase their likelihood of survival. Follow your protocols, just understand their impact. Usually this is seen in studies as 30 and 60 day mortality.

Morbidity: Morbidity means how many people got sick, injured, or had complications, even if they did not die. Understand the difference between morbidity and mortality. This is important in military medicine because there are plenty of Disease Non-Battle Injuries (DNBI) that impact medical readiness and keep soldiers down for days or weeks but don’t necessarily kill them. A soldier may not die of diarrhea, but it can be so severe that they are unable to work for days at a time.

Bias: Medicine isn’t perfect. If a cereal company funded a nutrition study on why cereal is the very best way to start your morning… there might be a reason they would want data to show positively. This is obviously rare, but this is why peer review and other factors can help mitigate, such as replication of the study by others who aren’t as involved or related. It is also important to note that all of these statistical tests can be skewed with small sample sizes. Having incredible stats is easy when you have only 10 patients in a study.

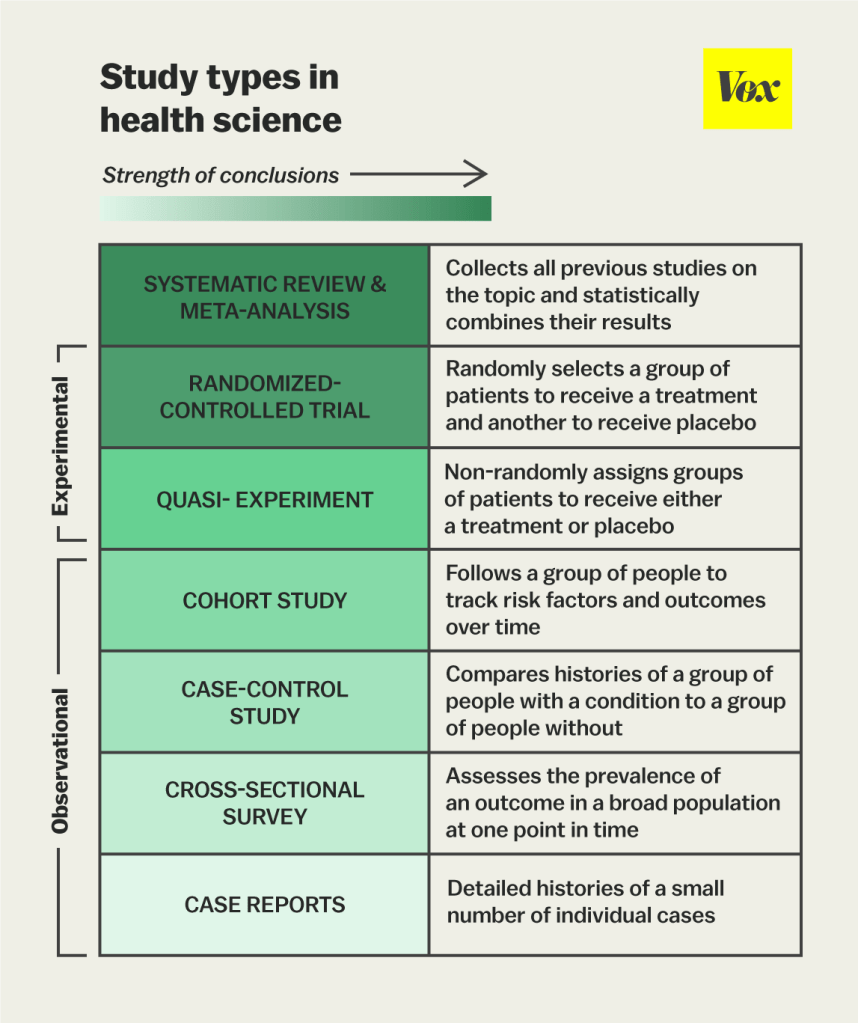

Pyramid of studies –

Source:https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/prevention_and_community_health/types-of-studies

Just because you are shown two studies on a topic, doesn’t mean they are the same caliber. Evidence is ranked by how trustworthy it is, starting from the bottom of the pyramid as lowest. Those are expert opinions, case reports, and small observational studies, which can be based on just a few patients. That could lead a novice reader to assume that each case will be exactly like the few cases mentioned, when it could be a rare occurrence or variability. Stronger evidence comes from larger cohort studies, then randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and at the very top are meta-analyses that combine multiple studies to find common ground. However, even meta-analyses may have weaknesses depending on how they are interpreted, as well as weaknesses of the RCT’s that they use. For now, understand some are not perfect, but tend to be stronger the more you go up.

The chart below can explain the sections above briefly better than I can.

(Source: https://www.vox.com/2015/1/5/7482871/types-of-study-design )

“So what does this mean if I am reading a study that is not a meta analysis of multiple RCT? It doesn’t matter?”

You have to understand where a study lies to be able to estimate its role. If someone shows you a case report, it doesn’t hold the same strength as an RCT would. If someone shows you an RCT on a topic, try to find other RCT’s or even a meta analysis of multiple RCT that take into account strengths and weaknesses. Some RCTs may not make it into a meta analysis because of their weakness, so the study you are reading may be one of those that can be cherry picked to represent an inaccurate viewpoint because of the data.

Some things in life, especially in combat medicine, do not have a clear evidence based answer and why expert opinion may be leaned on at times. This doesn’t mean to NOT trust expert opinion, just understand it may be subject to change when those experts are exposed to more accurate information down the line. Bottom line is, don’t get attached to information, only what is best for your patient.

If you learn in school that an intervention is good or bad, and later on are shown it’s opposite, then it only benefits your patient to consider the degree of impact and timing of your interventions.

Additionally, there is a difference between two providers who both do an intervention, one believes they must do an intervention because it helps, and the other does one because limited data may support but not the greatest. The difference is that one provider won’t beat himself or his students up if that intervention was not as prioritized as others during patient care.

Two identical patients with identical treatments can have different outcomes if certain interventions were performed in different order due to delays. While an emergency room can do 15 things at once and have 10 providers on one patient, prehospital care tends to have less resources and bandwidth. Therefore, providers can impact patient care by prioritizing interventions that help outcome first and they do that by knowing the evidence that supports their guidelines. Additionally, knowing the importance of interventions helps us mentor and train young medics because we know how important an intervention is. While attention to detail is a great thing to train, we can’t treat the medic who didn’t put a small dressing on a scrape the same as a medic who didn’t give their patients blood until 34 minutes into the scenario. Both get feedback, just of different severity because we know what interventions are more important. This in turn creates better clinicians instead of just technicians who view patients as “checklists” where every single intervention carries the same weight.

TRAPS

Second Opinion – While humans are obviously imperfect at aggregating data and interpreting it, if you are unsure of how to interpret it, then you can send it to a few senior medics or providers and ask what they think after you have read all of it and not just the conclusion. Eventually you will use the tips they showed you to be able to “poke holes” in them yourself.

If you send it to a peer, consider asking them what they think without giving your opinion so it doesn’t sway them. If giving it to a higher level provider, show you did your diligence by reading it all first and summarize what you got out of it so they can confirm or help you out.

Of course, another easy way out is to put the full paper into an Artificial Intelligence app, such as chatGPT and ask the study about its weaknesses and relevance. Sometimes you specifically have to ask it to be skeptical, or it may have a tendency to portray it in a more positive light or summarize it. Don’t just rely on the results, actually learn why ChatGPT suggested it’s weaknesses and confirm them yourself because it can also make mistakes like us. This is why another providers opinion may still help even after using AI tools..

Example: “Please analyze this study for me. Tell me how accurate it is and what weaknesses there are. Please be skeptical about its findings. Explain if this is relevant to my patients and practice as a combat medic.” You will be surprised at how well it breaks things down.

Be wary of “hallucinations” where AI tools will invent studies to support your claims, this can be prevented by asking for a DOI and study name if using AI for direct research on a topic.

Tying it all together:

We hope you save this page to come back and use this acronym to briefly screen studies so that you can begin to filter out some of the lower strength considerations. The more you are exposed to good and bad examples, the more you will grow. There is a lot to it, don’t feel intimidated or overwhelmed, just lean into it and stay skeptical.

Once you learn the information, remember we are treating humans and not numbers so there are times when we may have to both include the data, our operational environment, and even the patient’s wishes and desires. Without those factors, AI or a vending machine could make all of our decisions. It’s up to us to synthesize all this and bring it together to help do the most good for the most people with what we have available. Medicine is ever changing. It’s up to you, the provider, to keep pace with new information and to apply it as needed.

Additionally, providers you talk to about grading studies are probably more familiar with “PICO”, helping you identify the Patient, Intervention, potential Comparison, and focus on meaningful Outcomes like mortality or morbidity.

If something isn’t clear or you believe it is inaccurate, please reach out so we can improve this resource. Thank you for your contributions.

Remember to check for TRAPS in studies!

If you want to practice, take a look at these few studies, using the article above, to see what the limitations are. At first sight, they may look good, but with your new tools these should have some points that may not make them as accurate as possible.

- Analysis of tourniquet pressure over military winter clothing and a short review of combat casualty care in cold weather warfare (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10062217)

- Analysis of the effectiveness of prehospital blood product administration vs crystalloid infusion. Practice Tip: what is a possible “confounding variable” in the methods? (https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanhae/article/PIIS2352-3026(22)00040-0/fulltext)

- Analysis of Ketamine and its effects on cerebrospinal fluid pressure, this is one of the studies that was used to argue against ketamine for TBI patients. See if you can find out why it is no longer considered valid. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0007091217489628)

Here are a few examples of great studies that mention their own strengths and weaknesses. Try to pick out what the strengths and weaknesses are before getting to that section, or go back and look at how it could influence the numbers.

- – Association of Prehospital Blood Product Transfusion During Medical Evacuation of Combat Casualties in Afghanistan With Acute and 30-Day Survival ( https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29067429 )

- – The famous CRASH-2 trial (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23477634)

“This is too basic, I want to read studies like a pro”

These simplify critical appraisal:

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

Free PDF checklists for RCTs, cohort studies, case-control studies, etc. - JAMAEvidence: Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature

Offers decision trees and tools for evaluating bias, power, and more. Better for advanced medics. - Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM, Oxford)

Practical how-to’s on interpreting confidence intervals, absolute risk, odds ratios, etc.

Excellent one-page explainers for instructors or medics training others.

Authors:

Collin D, SO-ATP

Jeffrey Hoffman, BS, NRP

And help from multiple editors to facilitate!