Author:

“T” – Ranger Medic

Editors & Contributors:

Jon S – SOIDC, Ian Richardson – PJ Instructor,

Collin D, SOCM, JL McCarthy, SOCM

… and all the giants who came before and mentored us.

Outline:

- Introduction

- Training Objectives

- Designing the Patient

- Running the lane and roleplayer

- Manikins vs Roleplayers

- Grading the TCCC Lane

- “How much should we talk to the medic during lane?”

- How to provide feedback

- “Should Instructors use checklists or grade sheets?”

- Pearls, and avoiding common mistakes

- Implementing Additional Stress and Complexity

- What would you add?

- Appendix A: TCCC Skills Progression by Training Level

- Appendix B: Sample 1-page Checklist

- Appendix C: Sample 1-page Overview

- References

____________________________

Introduction

The intent of this guide is to empower medics with some framework to help them provide better training. Developing beneficial trauma lanes for training is a skill that has to be developed over time. It is not enough to randomly slap wounds on a patient and see if the medic can correctly treat them. Likewise, a mass casualty lane with a solo medic and 20 casualties has no purpose other than to overwhelm the medic. There is an entire article on why “too much, too soon” is a waste of time,1 so this will be expanding on how to do trauma lanes correctly once your team is ready.

Every lane that is developed should have a clear and testable training objective, and the trauma simulation should be controlled by the lane grader in a way that drives the medic towards this training objective. Furthermore, a lane proctor should strive to make every lane realistic and applicable to what the medic will see during his duties, because this type of training can dramatically improve performance in combat.2,3 The challenge lies in moving beyond rudimentary training exercises to develop true medical expertise. Special Operations Forces (SOF) instructors know what separates good medics from great ones: it’s not just methodology, but the unwavering belief that higher standards are achievable for any medic willing to put in the work under the mentorship of an instructor who truly cares about their success. Unfortunately, common training practices often fall short of this ideal. Many trauma training scenarios lack clear, testable objectives; they devolve into “kitchen sink” events that overwhelm learners with an unrealistic number of injuries rather than fostering focused skill development; evaluation is often subjective and inconsistent; and feedback is frequently unstructured and ineffective.4 This creates a significant “training gap” where medics may learn the steps of a procedure but fail to develop the adaptive expertise, critical thinking, and psychological resilience required to apply those skills effectively under the extreme duress of combat.

____________________

Training Objectives

I cannot overstate the importance of running trauma lanes that have a purpose.5 The purpose of the lane should be to test the training that you have implemented recently. Did your medical section give a class on airway management this week? Your trauma lanes should be designed to test the medic’s knowledge of your airway protocol. Most of the time when I choose a training objective, it is broadly the protocol I want to test. Therefore, to be a great instructor you must thoroughly know and reference the TCCC guidelines on Deployed Medicine app and website, JTS Clinical Practice Guidelines, and unit internal SOPs in order to create scenarios that test them. You can’t expect a medic to handle a scenario that you don’t intimately know yourself.

As an easy example, let’s say your medical section received a class on damage control resuscitation this week. Your easy training objective is to test your medic’s understanding of your damage control resuscitation protocol. Next, I choose critical criteria before the lane. These critical criteria are the things that must be accomplished or the lane is a failure. I generally stick to choosing ~3-4 critical criteria per lane, and definitely avoid choosing more than five. This is less about the hard number and more about making CRITICAL criteria about the heavy parts that impact patient outcomes. If you’re consistently putting 11+ critical criteria in a lane, then consider that “when everything is critical, nothing is.”6 You can still debrief them and expect better when they mess up tasks outside of critical criteria. We first have to personally know what the MOST important things a medic does well are.

For our example, some easy critical criteria could be:

- Gain and maintain hemorrhage control

- Administer 2g TXA

- Administer 1 unit of blood within 30 minutes

- Evacuated patient without delays

Some common sense is required here. If during the execution of the trauma lane the medic creates a situation that is unsafe for the patient or potentially causes severe harm, he has obviously failed the lane and this needs to be addressed. However, when developing your critical criteria, it is a waste of bandwidth to attempt to imagine every critical mistake that a medic might make. Choose a couple that align with your training objective and move on. You could also have standing objectives per unit SOP for every lane developed, such as causing potentially lethal/maiming harm, or losing accountability of serialized items, etc. Remember to develop the critical criteria beforehand, because not doing that leaves room for subjectivity, improper grading or personal attitude towards the individual to cause the instructor to move the goal post closer or further away.

If you did not teach a specific class recently, or taught many, then you can choose from more skills or objectives they should already be expected to know and self-study. The risk of putting objectives in a lane they haven’t been expected to know yet is fumbling a training opportunity.

____________________________

Designing The Patient

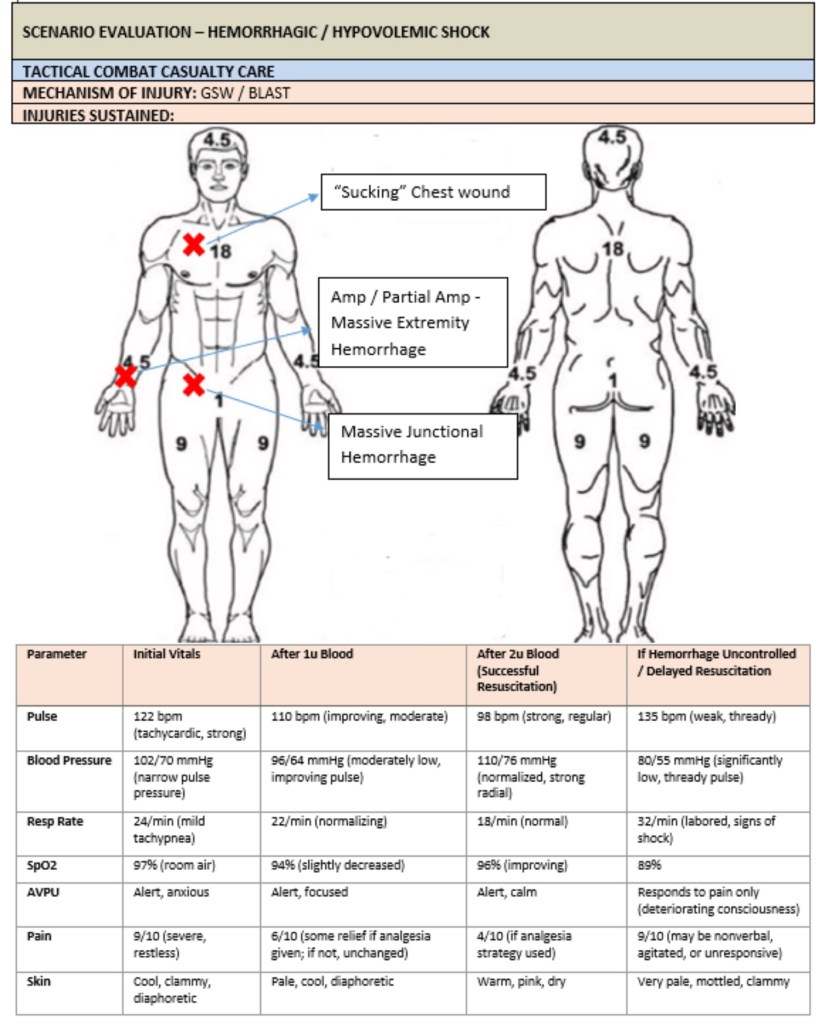

The next step is to intentionally design the wound set of the patient and pre-plan how the patient will trend based on the decisions the medic makes and the actions he takes. Again, it is best to keep this generalized and simple instead of trying to predict everything the medic might do. For example, if the medic does a good job, the patient will trend positively, or the patient will initially respond to one unit of blood and then down trend after a set period of time. While infusing the lane with complexity, however, it is important to remember the critical criteria you put in place and avoid over complicating the lane or creating no-win scenarios. If your purpose is to identify whether or not your medics have the ability to recognize transient responders to resuscitation and continue resuscitating as indicated, your training objectives and critical criteria should reflect that. Don’t let the good idea fairies distract from your intended purpose. Also keep in mind how often injuries occur so we focus on the more likely wounds. Patients should often have extremity and/or junctional bleeding since those are more common causes of death we can work on.5 Eviscerations, burns, fractures, tension pneumothorax and lanes with only internal hemorrhage happen and can be implemented but need to not be the focus, especially in a new medic who hasn’t shown his ability to perform excellent TCCC yet. Most medics know the 2001-20117 study, but there are two new studies showing common injuries more clearly, one specific to Rangers8 and one in special operations.9

For example, Let’s say you want to test him on proper tourniquet application (and time), wound packing and blood transfusions; we would make a wound on an extremity, add a junctional injury (on an exact location where we can feel that artery pulsate), then give our medic vitals that lead them to doing a blood transfusion after he assesses his patient.That is a good 2-3 critical criteria. They don’t need to do something intense for every letter of MARCH and PAWS. Stick to 1-2 bleeds and another intervention for the most part. Consider only 1–2 major injuries max per patient (especially CLS or non-US Partner Forces). Overloading lanes creates chaos, not learning.4,6

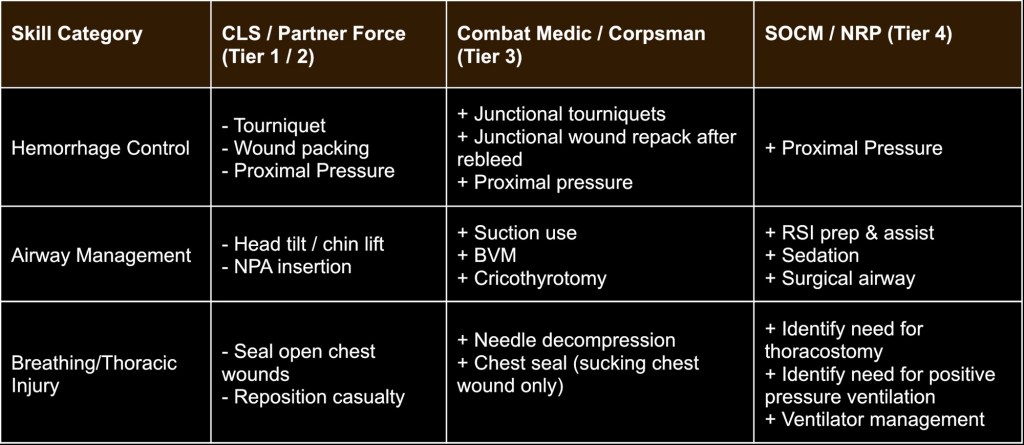

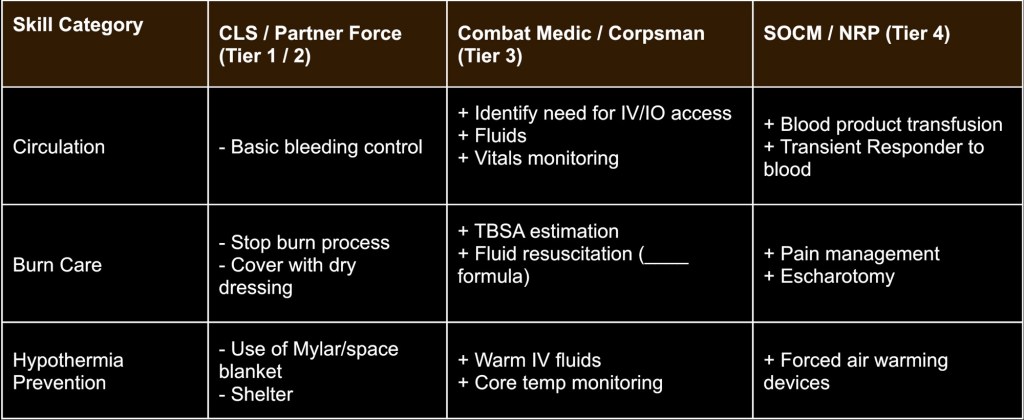

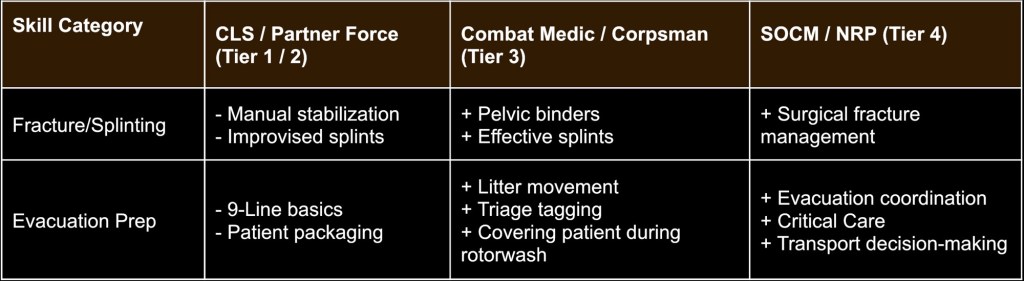

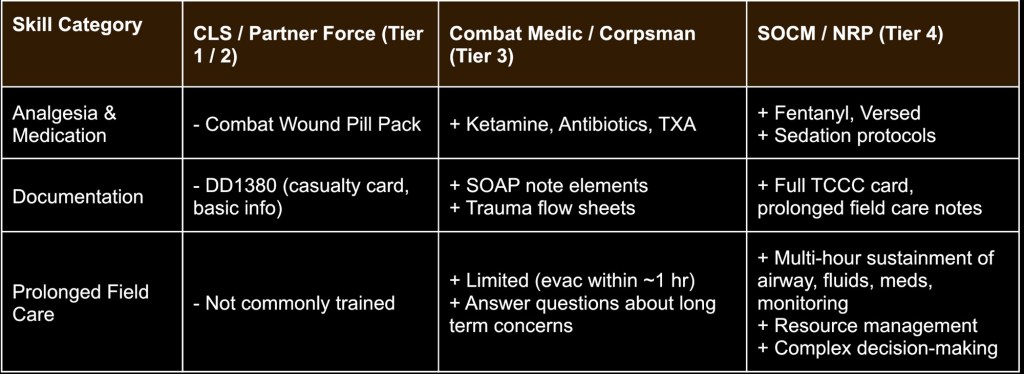

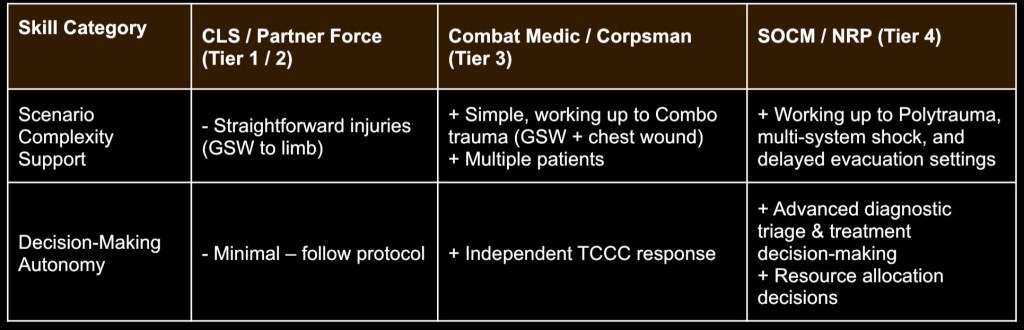

The skill level of the medic should also be taken into account when designing trauma lanes. A brand-new medic from AIT might be easily overwhelmed with a true multi-system trauma patient in a dynamic scenario requiring multiple patient movements on a compressed timeline. However, a senior Ranger platoon medic preparing to take over as a company senior medic will accomplish this lane while smoking a cigarette and rolling his eyes at you, and will do it faster than your 2 mile time. It is your responsibility as a leader to know the skill level of your medics and challenge them appropriately. See Appendix A for an example shared with us of one unit’s SOPs for creating scenarios and backwards planning. It’s not perfect, just an example a school or unit could use to help new instructors. You can use this to create one that suits your operational environment and demographic.

Remember, as instructors we must always consider the demographic we are teaching. A partner force military in Africa will not have our same Class 8 medical supplies, so we may have to teach regular gauze and improvised supplies instead of thousand-dollar IFAKs. An Infantryman does not need to cric, so just because you know it does not mean you need to teach it. Try to think of just who your students are and how proficient they are before planning classes. Additionally, A.I. is a useful tool but if you don’t know what you are doing, you might not catch a mistake it makes, so be cautious and double check what it produces.

_____________________________

Running The Lane and Roleplayer

It takes some experience to properly brief a roleplayer to add value to the experience. You want to ensure someone is giving a realistic portrayal of a patient, without trying to win an acting award for exaggeration. While you can’t expect a roleplayer, even a medic, to predict all the proper responses, you should give them a general course. “When they find you, you’re doing ____. Give me your impression of that.” Then provide feedback or a personal example. You can also give them a few examples of what it might progress to, or things to do on their own, “every time he does ____, you need to be in pain.” You can have the roleplayer brief this back to you. If a presentation is particularly important, give them an example and ask them to give you their attempt.

During the lane there are a few ways to provide feedback. Whispering in the ear is the lowest fidelity for last minute feedback that is complex. For predictable evolutions in the scenario, you can get casualty’s attention with a tap and use hand signals as part of an internal SOP to get them to do something like pass out, struggle to breath, get nauseous or other similar reactions.

A higher fidelity option is bluetooth earbuds (maybe not expensive AirPods) placed in casualty temporarily to talk to the patient through text-to-speech on phone, Consider over-the-ear hook or or tape/secure in place if patient movement isn’t intense to keep in place, or remove between movements. If this fails, fall back on briefed hand or arm signals.

_____________________________________________

“Does it matter if we use manikins, or should we use roleplayers even if they are harder to acquire?”

You should emphasize roleplayers, and fight to acquire them for most TCCC training. Manikins are low fidelity, they don’t do many things well.10 Some may lean on manikins because they are easy to reuse and the cadre do not need to convince someone to be patient and get poked. Outside of expectant casualties, or high risk such as live shooting ranges, and high angle/hoist training, manikins should not be the main model used. This means more effort on instructors to fight for roleplayers, although it’s worth it. If you have multiple medics around for this training exercise, then choose one of them to be patient, then they can rotate. If you just did lane as a medic, next round you are the patient. Medics make decent casualties, anyway.

Roleplayer may be more stressful for the instructor to plan for, but the benefits of anatomical realism, feedback on real vitals, IV access and pelvic binder placement are worth it to the students. While roleplayers can not receive surgical skills, most manikins don’t have high fidelity with surgical skills, either. So if you want to test crics, I.O. ‘s and other things with a roleplayer, then have training devices nearby that are available. That way the medic uses a permanent marker to place the location of their cric, I.O., or thoracostomy. Even if they do it well on the trainer, give the patient feedback based on where they placed the intervention on the roleplayer. For instance, if they placed their permanent marker spot for a tibial I.O. on the anterior tibialis muscle, then what is pushed may not be working. If they don’t re-assess the site for infiltration or didn’t check for bone marrow, then they may miss this, even if they easily nailed the landmarks of the low fidelity I.O. trainer that already had 40 holes of where they should go.

Intravenous access is another benefit to using roleplayers over manikins or low fidelity training models. The most expensive manikins simply do not provide the fidelity of a real arm on a very important procedure required to get blood on board. However, your medic may make the clinical decision to go intraosseous due to severity of the wounds. A way to reward clinical thinking while still grading a medics IV skills is to have an SOP that before the lane ends, they must have patent access. This way they can still practice clinical decision making, but it also means they aren’t saved from poor IV skills. Some medics may not be getting lots of repetitions, so it is a waste to deprive them of another opportunity, plus the ability to receive feedback. The Special Operations Combat Medic Skills Sustainment Course (SOCMSSC) Cadre may sometimes utilize this method.

Hemorrhage control can be difficult to grade on manikins and roleplayers alike, even if using a wound packing moulage that has a blood pump or not. The instructor must be highly attuned to constant pressure and note every single second the medic lets go with fingertips to do something or shift. It can not be overstated how important this leading cause of death is. Common issues include releasing pressure on gauze while packing, so ensure you are watching medics fingertips. Even a slight moment of letting go causes gauze on the injured vessel to soak and become less effective. Since wound packing is notoriously easy on manikins and roleplayers, one way to add training value is to discretely soak the dressing with fake blood while the medic is working on another part of the patient. This shows if they are reassessing their work, and if they do find it, their ability to make the decision to repack instead of just adding to a failed packing.

Mental status should also be briefed to the roleplayer accurately. Think back to a time you saw a person who wasn’t fully alert, after a ruck march or while not feeling well. If a medic asks, “hey buddy where are you at?”, the patient shouldn’t be saying “banana.” Instead, have patients do long pauses to think, lots of “uhm”, and slower confused talking with less eye contact like they are genuinely trying to answer. If the roleplayer says something that isn’t fitting to where you are driving, it may be a rare excuse for the proctor to interject, “He doesn’t say that, he says ______.” This is best mitigated through briefs and communication during lane.

Do not place tachypnea only in tension pneumothorax lanes. If your patient loses a lot of blood, chances are that they will be breathing faster. If you only have the roleplayer act out tachypnea during TPX patients, they may be confused when their real hemorrhagic shock patient is breathing faster. We want medics to focus on the needle in the arm (blood transfusions) before the needle in the chest.

Ultimately, the usefulness of the model is only as good as the instructor.

For brevity, we will skip moulage creation and more in depth model analysis to keep this short and focused. Training does not need to always be done on high fidelity moulage and sims. A good medic should be able to run a shadowbox lane on a patient with no injuries, or even a full trauma lane with simple 2” white medical tape used to mark injuries. Fidelity of moulage does not impact tourniquet time or tightness. Now we will move on to evaluating a medic during the lane, and providing feedback after.

_________________________________

Grading the TCCC Lane

The system in which you grade and give feedback to medics is just as important as the way that you design the trauma lanes. I think it is very important to keep AARs quick, concise and without fluff. You should not be interested in listening to a junior medic stutter through telling a story of everything he did during the lane for the next 30 minutes. You should also not allow someone to justify failures by explaining what they were “trying” to do or what they “thought” was going on. You created the lane and set the standards. If the medic did not meet the standard, respectfully identify it to them and explain what you want to see in the future. We are in the business of providing first line care to combat casualties. People’s lives depend on your ability to give clear and concise feedback that helps your medics grow, feelings should not play a part in this conversation.

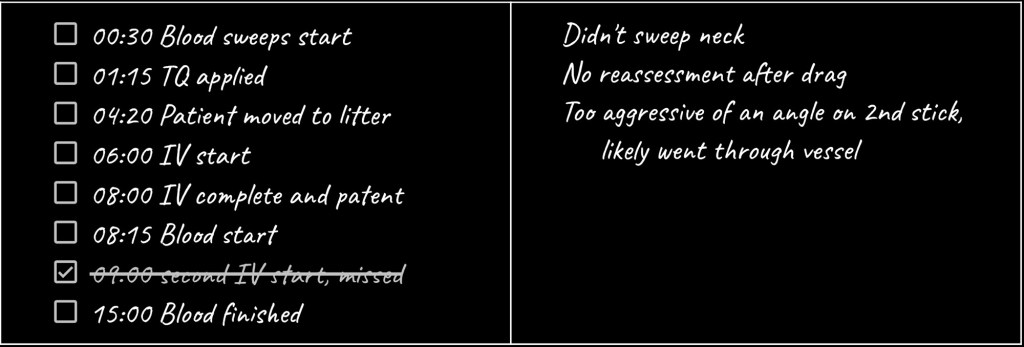

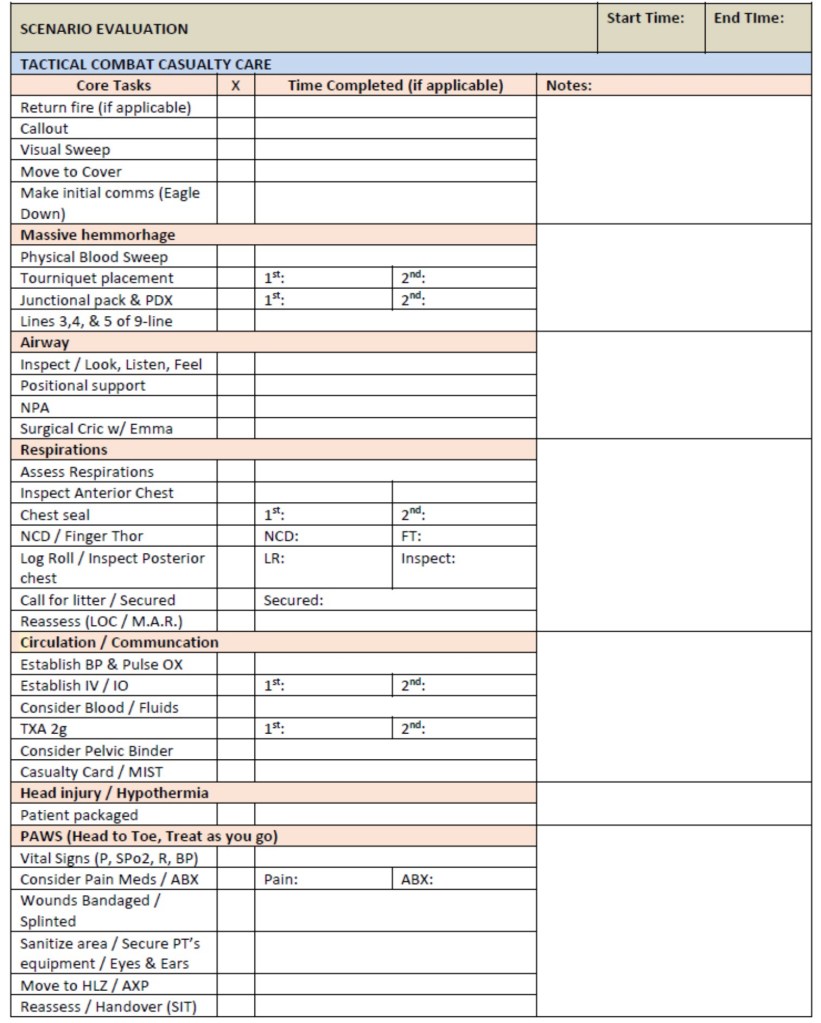

The easiest thing to help you give this clear feedback is taking extensive notes with time stamps throughout the lane. I generally keep detailed, but simple notes on everything the medic does with start time and end time. If you looked in my notebook the notes would look something like this or see Appendix B at the end.

If there is a major mistake, I annotate it next to the skill. If I have a thought I want to say at the end I also write that down. Time stamps are a mandatory part of grading TCCC lanes and interventions as written above, not just the final time of the entire lane. You can have a great lane time overall, but a 5 minute IV time, 4 minute cric, or similar slow intervention time. If an Instructor fails to track time, they can not show a student how slow that intervention was to provide feedback. This means a student does not get an opportunity to grow. With some sources suggesting a ~5% mortality11 impact per minute with delays in resuscitation of some trauma patients, every minute counts and we should be avoiding small interventions that delay blood. Every minute spent chasing needle decompressions or fumbling with gear is room for improvement.

“How much should we talk to the medic during a lane?”

You shouldn’t, minimize as much as possible. Will you be there in real life talking to them? No. This isn’t a game where you happen to be there, this is you proctoring a lane to simulate them being alone. You should hopefully only be providing minimal feedback when giving only the vitals they took back to a medic after he gives you what he has on the roleplayer. He shouldn’t be looking at you, he should be assessing and looking at his patient. Additionally, you should have vitals and general presentations for each phase of the lane for easy reference (Appendix C).

For example:

Medic, looking at patient: “I have BP as 118/74, pulse is 82, strong and regular” (does not say “what is my BP”)

Proctor: “BP is 92/60, 112, regular, difficult to feel.” (Does not give more than asked, such as skin color.)

Training issue: Students tend to latch onto words like “weak and thready.” Be careful leaning on words that let them not think. Leaning on buzzwords may cause them to rely on strength of pulse alone, which is an inaccurate identifier of shock. Therefore full vitals and looking at patients skin and overall clinical picture are important. It is possible for patients to have a radial pulse but other vitals point to them still needing blood.

Some instructors use a haptic app on their phone then put students’ fingers on the back of the phone. This way they can feel the vibrate on your phone for what it really is. This is if you want to test them on their ability to accurately count if it’s a brand new medic without much hands-on experience. Instructors should also check the roleplayers opposite wrist to see if their pulse count was accurate.

Excessive feedback can derail their lane, although some “stop-and-go” debriefing during training can be an effective method of debriefing in rare cases of new medics needing assistance.8,9 If you’re having to step in often, then there is either a safety concern, or the medic has gone off the rails to the point that you are having to step in to help guide training value out of an already failed lane. Instead of watching the failure continue to misery, you can provide guidance to get them back on trajectory to see what else they need feedback on. At this point, the lane is already a failure but you are giving them experience to continue the rep. An experienced provider may make the call to end the lane if something is egregious enough (failed initial hemorrhage control), or to “reset scenario to before fatal mistake” if wanting to continue a lane that has a lot of resources invested (vehicles, prolonged field care planned later, etc.)

However, this contrasts to teaching individual interventions or basic TCCC sequences in a classroom where cadre should be immediate, tactile feedback.12 When someone is brand new to an intervention, practicing they should have immediate corrections. Procedures should be nailed in a calm classroom before escalating1 to expecting them to do it under duress in a lane. Poor tourniquets and wound packing in class won’t suddenly “click” because they are put in a stressful TCCC scenario prematurely. Get it right, then escalate. Do not skip steps.

___________________________

Lane is over, time to provide feedback

At the end of the lane I assign it a grade on a scale of 0 to 3. 0 is failing, 1 is marginally passing/needs improvement, 2 is acceptable performance, 3 is exceptional performance. This grade is pretty subjective, so it is important to be able to refer to your notes and clearly identify for the medic why you have assigned the grade.

A grade is far better than just a checked box on a checklist, or simply a pass or fail. You should also consider grades for interventions themselves. For example, if one medic puts on an HPMK 11 minutes into a scenario and leaves the patient halfway exposed after every procedure, but another medic gets them covered 5 minutes in and keeps them wrapped up. They both “check the box” the same on a weak checklist and look like they performed the same. However, the first medic would get a “1” and the other gets a “3” in the Hypothermia management section. We will discuss checklist pitfalls more later on.

The final part is giving feedback. This might seem counter-intuitive, but I believe less detail is more here for most. In my opinion, it is not beneficial to nit-pick every single mistake a medic makes throughout a lane and give them a laundry list of things to improve on. By the time you get to correction 13 of 25, the medic may have forgotten the more important aspects that really need work.13 Instead, I try to attribute patterns of mistakes to overarching themes that the medic can digest and work on. If it is possible, I strive to leave the medic with actionable core concepts to work on and bring into their next lane.

Here is the easiest example I can think of:

You ran a trauma lane for a new medic. He is nervous to make a good first impression and it shows. He struggles throughout the lane to overcome stress even though you have implemented very little external stress into the lane. He struggles with most of his skills including fumbling an IV, dropping equipment, “yard sales” his aid bag and has an extremely difficult time communicating with higher, and during his casualty handover.

Instead of listing out every tiny thing this nervous and exhausted young medic did wrong, try to tie it to one over-arching theme that, if improved, will solve most of his problems. For this young medic his theme is composure. If he can keep himself more composed, all of the mistakes he made will improve on the next lane. This is easily the most common theme I see with new medics. Outlining the countless mistakes made throughout the lane is the most common mistake I see made by new proctors.

Additional common themes I assign to medics are: failure to prepare equipment, unfamiliar with equipment you are carrying, failure to properly assess (or reassess) patients, loss of situational awareness, no command presence, etc. Your imagination is the only limit here, but it is your job to identify why the medic is making these mistakes so that you can help him overcome them.

________________________

“So we shouldn’t discuss every single thing they do wrong? I am worried my medic will think that this scenario is too easy or they did better than they really performed.”

As Instructors we should still be strict and track every room for improvement to see how it adds up, but we don’t always need to emphasize every small point verbally, especially not harshly, nor equally. A medic that is sloppy with a tegaderm application did not have an issue as big as mishandled life threats. On the other hand, there is also no value in a pat on the back for a “good enough” trauma lane, so everyone should get feedback to grow. Most of us need proper feedback to grow, otherwise the lane isn’t of value. However, not giving every tiny piece of feedback you wrote down in notes to a new medic that did dozens of things wrong is less about not sharing and more about giving him actionable ways to improve the big wins without focusing on the wrong things. This is assuming they have a receptive attitude and are taking it to heart.

Attitude plays a large part in the debrief. Most medics are coachable and want to perform, so they will take it seriously if told they did poorly on many things and could improve in multiple ways. That alone in an aspiring high performer can be ingrained into a lasting memory. However, if you have a medic who digs their heels in, does not believe what they did was a big deal, defends it poorly or has an overall bad attitude, then you have the ammunition through your notes (or even recording) to further define multiple missteps and tally up the minutiae. However, you may also have to consider cultural issues of where a medic is working if training and performance is not held at a premium.

A great instructor can articulate complications, risks and impact to mortality through poor and delayed interventions to drive home why it’s important they don’t make that mistake, besides “you didn’t check the box”. For instance, a rushed finger thoracostomy with no regard for even attempting to be somewhat clean, and forgetting to give antibiotics after could lead to empyema, an infection in the chest. If they are arguing to save a few seconds by not cleaning, then perhaps the main effort is practicing the procedure to save those seconds through technique instead, considering needle thoracostomy first if the patient is that unstable that they can not wait, and understanding long term sequelae of being sloppy.

___________________________________________

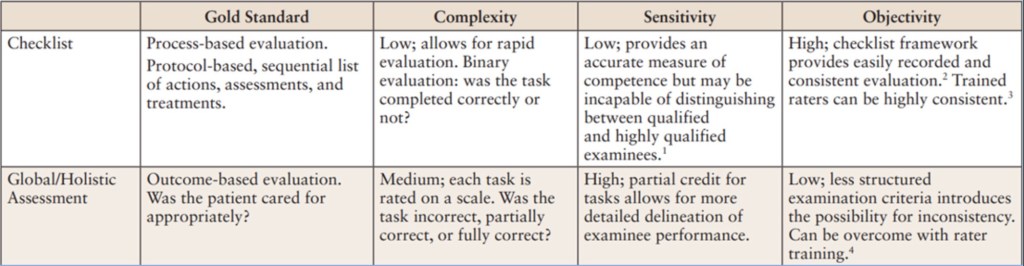

“Should Instructors use checklists, or grade sheets?”

This is going to be controversial, but stick with us. An elite instructor will not NEED a checklist to provide a great quality lane, but most instructors probably still need them, at least at first. For the majority of instructors that are not in elite organizations supported by multiple deployment experiences, a checklist can become a black and white law that could cause us to pass poor performers or fail good performers.14

If your organization uses a checklist, we highly encourage you to get together as Cadre to ensure it is adequate and there is room for good medicine; Establish a scoring system or grade instead of a checked box, with time hacks for each section, and individual interventions themselves. We already discussed the benefits of assigning a grade instead of checking a box above so no more on that point. On the other hand, a well done grading sheet can help new NCO’s and novice instructors without much conscious experience to give students a fair, consistent examination without forgetting key concepts. A weak checklist makes even senior instructors focus on less important details instead of key concepts, holding them back from growth as a proctor. You see this when medics run a great lane, but the instructor is berating them over something minimal they did that’s not as serious as a failed hemorrhage control attempt or a botched cricothyroidotomy. The truth is a good instructor will know that everything on a checklist is not equal, and some things save more lives than others.

However, one consideration for checklists is for pre-deployment validation, specifically failure. If you have to fail a medic and remove them from a platoon/team due to massive failure, then a checklist provides more ammunition to discuss this with leadership that won’t want to lose a medic. Non-medical chain of command may see the medic as still deployable and may take convincing that they need retraining. This can become even more serious if the validation exercise is scheduled too close to deployment to consider a replacement medic or even retraining, so plan this out in the training calendar. Checklists also show leaders reproducibility as in, “All the other medics can do this, but he failed these multiple points and needs retraining, or removal from the line.”

Bottom line up front: Recognize checklists are limited tools that need to be honestly scrubbed for accuracy. If your Cadre notices that students are doing bad medicine yet technically passing the grade sheet, or critically thinking but failing, then find ways to enable what is best for patient care. Checklists are not the gold standard in most cases. However, most medic instructors do not have the experience or education to properly grade a lane without some guidance, or they may be forced to use them due to unit/schoolhouse SOPs. Therefore, If you’re going to use one, make them better.The table below provides characteristics of commonly used evaluation methods in medical training.14,15,16,17

_________________________________________________

Pearls and avoiding common mistakes

Kitchen Sink Wounds: More ≠ better. If you want it more difficult, be more strict with evaluating the interventions you are giving instead of adding more. We want better medics, not just more busy ones. For example, instead of adding the need for a third or fourth tourniquet, consider addressing why the first 1-2 took 40-50 seconds each, and that they did not remove roleplayers’ pulse.

Too much verbalization or “finger drilling”, especially with medication: You need to perform interventions, not say them. A common reason for lane failures or mishaps in TCCC is improper medication administration. Even if they verbalize the proper dose, they may draw up a different amount and push it. You should be using saline vials with fake medication labels so they can practice Ketamine, TXA, calcium, antibiotics and more. Verbalizing interventions like this is a massive missed opportunity. If your unit provider is not cool with you giving IM or IV meds to your roleplayer, then administratively push it into dirt next to the patient so medic can at least practice math be graded on the amount given. Without implementing this in training, instructors can not see if the medic is slow, bringing improper supplies to perform draws, or giving wrong doses under duress.

Anatomical Nonsense: A “junctional” bleed in the thigh isn’t correct. If you want to place a junctional or arterial bleed, you should palpate that artery as an instructor. If you can’t find the artery quickly, you need additional practice before teaching. Your students should be able to quickly identify arteries to hold proximal pressure with fingertips if needed, so you should be able to do the same within seconds.

Additionally, You can’t use a scalpel or real needle on roleplayers, but you can hand the medic a marker to draw the location of the the intervention on the roleplayer, then perform procedure such as a cric or I.O. on a training model next to the roleplayer. Avoid wearable procedure trainers unless they have a kevlar backing to protect patient from the scalpel.

Speaking of anatomy, an estimated ~43% of pelvic binders are misplaced. Instructors should always palpate greater trochanters when lane ends, unless it’s obvious without palpation that it’s far too high.

Excessively crazy roleplayers: Medics don’t need cartoonishly psychotic patients to feel stress. While there are rare psych patients that add duress, consider the limited training value or adding stress through other ways. If you are dead set on including psych patients to account for the rare situation, ensure there is a solution that adds value and that the medic has been trained on that before. This could be the patient being given a task, location to stay in or being handled by a non-medic, after being directed by a medic. Continually pestering, not being allowed to be touched or escaping “restraints” after initial management is of little to no value. We are here to show medics what good management looks like, and not just surviving chaos. We can provide a future guide like this on running MASCALs.

No Clear Goal: “I just want to add these wounds see what happens” = lazy training and a waste of time.

The “instant” Tension Pneumothorax: There is an epidemic of instructors giving severe respiratory distress to a patient with chest trauma just a minute after they are shot. The medic runs up to the roleplayer and they are gasping for air like they just finished sprints. The intent is to clue the medic student into recognizing the need for a needle/finger thoracostomy. While the attempt to teach an intervention, sequence and add stress has good intention, it does not set medics up for success. It takes a real patient not being ventilated with PPV awhile to build up to a tension, even if they really have it. Tension Pneumothorax is exceedingly rare in spontaneous breathing patients (those we aren’t breathing for with a BVM/Vent). Therefore, we need to teach new medics that a little increased work of breathing is probably due to blood loss and to consider that first. That doesn’t mean that severe lung issues such as blast lung can not cause respiratory distress in little time frames, it just means we focus on what happens more often to save more lives, with realistic time frames. Tension Pneumothorax is rare and takes time. We wouldn’t give sepsis five minutes after a papercut in a scenario, so why tension pneumothorax in a few minutes? Your medic should catch TPX later on (~15+ minutes) after reassessing tourniquets and bandages for bleed through.

The unwinnable dies-no-matter-what patient, AKA “Kobiyashu Maru”: The intent by instructors to prepare soldiers for the rigors of combat may have good intent, but it doesn’t work. Patients who die no matter what the medic does is of incredibly low value to 1-2 patient TCCC scenarios. This lesson could easily be discussed in a classroom to be driven home without wasting an entire trauma lane’s time on this factor. If we can not convince you not to do this and you are still hellbent on the patient still dying in a single patient TCCC scenario (Not MASCAL), then it must be just one small piece of many learning objectives.

For instance, Medic controls junctional bleeding, provides resuscitation, proper pharm administration, gets airway and then considers bilateral finger thoracostomy based on wound set. 95% of the lane should not be the value of “people die”, which does not take a genius to figure out. Training can not impart that degree of heavy impact, and certainly is not as important as scenarios we can train on how to SAVE lives. Additionally, the context of this scenario matters. If doing this in front of a group of medics as an evaluation, they may understand what is happening. If you decide to throw a “no win” scenario at a medic and his patient dies in front of his infantry platoon, you may ruin their reputation with the unit as they may see the roleplayers death as negative feedback due to medic messing up, which is morale crushing. Once again, being an instructor is mastering your craft and intentional context, not just random training and scenarios. If in a MASCAL, then of course expectant patients are a consideration because more is going on, but as the single TCCC patient it’s low value. If this is during PFC, then the lesson could be running and managing a code and considering H’s and T’s, ROSC management (yes they can code and come back) or even palliative care after telemedicine. This should be avoided, or one minor aspect of the training in this niche example of including it. Remember the first point in this article, training must have an objective.

Emphasizing the wrong criteria – Novice Instructors treat all parts of guidelines and checklists as gospel. The medic who made a minor mistake is treated as if he made a fatal mistake.

Senior Instructors must police their own to ensure uniform standards and equal grading. If you’re running training as an individual, you have to know what is truly important.

For example, There is a current training scar of holding gauze for 3 minutes during TFC all the time and delaying a pressure bandage. Pressure dressings count as holding pressure. Having a patient with exposed gauze is a liability if the tactical situation changes and a medic needs to move. There is no reason for a medic to ask leadership for a delay in movement due to an arbitrary 3 minute wait; pack immediately and reassess later. The 3 minutes comes from a pig study where they held pressure on pigs, but chose not to wrap or check after 1, or 2 minutes. An instructor that is unable to critically think beyond guidelines or a checklist may improperly develop a medic to emphasize the wrong criteria.

____________________________

Implementing Additional Stress and Complexity

There are definitely effective and ineffective ways to implement stress.4 I think that implementing stress in a lane should follow 3 simple rules. First, the stress you are implementing should be as realistic as possible. Following a medic around with a loudspeaker that’s playing “another one bites the dust” because you think the medic is doing a bad job is ineffective, and annoying. However, the liberal use of artillery simulators or recorded combat sounds is more realistic. In the perfect world for a high stress lane I would have an endless supply of artillery simulators and a machine gun team with their M240 (that works) and endless blanks. Achieving realism is difficult, but it should always be the goal. If you don’t have experience to know realism, then focus on the medicine and use this guide to avoid common training scars.

The second rule is that the stress should enhance training and not detract from it. The head injury example above is an example of detracting from training value.

However, let’s say that your trauma simulation takes place during a small unit operation where your unit is in danger of being overrun and is breaking contact. This lane would require you to work quickly, efficiently, and move urgently. This lane could include multiple casualty movements including buddy carries and eventually on a litter, and it could last as long as you need it to. I don’t know very many people who aren’t stressed after bounding 800 meters with a litter patient while trying to accomplish treatments and keep the patient alive. This is realistic and enhances the training, instead of adding stress for the sake of stress. The stressor becomes time and the medics own speed and abilities, as they may have 2-3 minutes of time to work starting the second the litter touches down. This 2-3 minutes does not mean stopping interventions and beginning to pack up, but already moving with litter up. This requires thinking of what needs to be done during movement and before litter is set down next halt, and not just slowly moving through assessments and interventions. They also have to think with an elevated heart rate. The emphasis is on medicine and not just excessive litter carries. There is not enough time for all medicine to happen in this scenario… so the medic must truly prioritize what a patient needs first and most while respecting the tactical situation.

The last rule would be to scale the stress you are implementing to an appropriate level for the medic you are assessing.1 The lane I design for a senior platoon medic looks much different than the lane I design for a brand new medic I just received from HHC. The wound set, training objective and critical criteria can remain the same, however I would not expect the new medic to be able to flawlessly execute this lane on the move as we bound with a litter patient for 30 minutes constantly having to move away from contact. It is my job as a leader to train this new medic until he can accomplish this. However, if my senior platoon medic who is up to take over a company cannot do this, I would not recommend he be chosen to take over the next available company. Stress is scalable, and the proper implementation of stress in trauma lanes requires that you apply common sense.

The goal or outcome of stress application during training should be to inoculate the medic to stress by allowing them opportunities to cope with stress in a controlled environment. Excess stress is detrimental to task performance.4,18 Stress coping techniques may be an effective method at improving performance under stress and something they can learn to implement.19 It’s our job to help junior medics develop these skills and show why they should be practicing skills and assessments on their own as an individual responsibility.

_______________________________________________________

What would you add?

Reach out and let us know if you have questions or comments so we can improve this document for those teaching trauma lanes across the force. If you need help refining SOPs for your Military Unit or School, we can provide mentorship to help you train like the best. Our patients deserve it.

Appendix A: TCCC Skills Progression by Training Level

Table 1: Core Medical Interventions

Table 2: Circulation & Resuscitation

Table 3: Assessment & Support Skills

Table 4: Advanced Care & Documentation

Table 5: Training Complexity & Decision-making

Appendix B: Sample 1-page checklist

Appendix C: Sample 1-page Overview

References

- McCarthy J, Lauria MJ, Fisher AD. A lost opportunity: the use of unorthodox training methods for prehospital trauma care. J Spec Oper Med. 2022;22(3):29-35.

- Ericsson A. Development of Professional Expertise: Toward Measurement of Expert Performance and Design of Optimal Learning Environments. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

- Gorman PF. The Military Value of Training (No. IDAP2515). 1990

- Cline P. White paper: re-thinking the development of the next generation of mission critical teams. Mission Critical Team Institute. 2022. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365628226

- Lockett C, Naylor JF, Fisher AD, et al. A comparison of injury patterns and interventions among US military special operations versus conventional forces combatants. Med J (Fort Sam Houston Tex). 2023;(Per 23-1/2/3):64-69.

- Richardson I, Lauria MJ, Gravano B, Swenson JF, Rush SC. The effect of critical task auto-failure criteria on medical evaluation methods in the pararescue schoolhouse. J Spec Oper Med. 2024;24(2):67-71. doi:10.55460/VG7D-H3WA

- Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S431-S437. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182755dcc

- Moore CH, Kotwal RS, Howard JT, et al. A review of 75th Ranger Regiment battle-injured fatalities incurred during combat operations from 2001 to 2021. Mil Med. 2024;189(7-8):1728-1737. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad331

- Kotwal RS, Mazuchowski EL, Howard JT, et al. United States Special Operations Command fatality study of subcommands, units, and trends. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(2S Suppl 2):S213-S224. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002699

- Bailey MS, Brannick CR, Llerena L, Lyons D, Tromly S, Whittier NC. Developing criteria to compare military medical trauma simulations across modalities.

- Duchesne J, McLafferty BJ, Broome JM, et al. Every minute matters: improving outcomes for penetrating trauma through prehospital advanced resuscitative care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024;97(5):710-715. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000004363

- Schober P, Kistemaker KR, Sijani F, et al. Effects of post-scenario debriefing versus stop-and-go debriefing in medical simulation training on skill acquisition and learning experience: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:1-7.

- Cowan N. The magical mystery four: how is working memory capacity limited, and why? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(1):51-57. doi:10.1177/0963721409359277

- Regehr G, MacRae H, Reznick RK, Szalay D. Comparing the psychometric properties of checklists and global rating scales for assessing performance on an OSCE-format examination. Acad Med. 1998;73(9):993-997. doi:10.1097/00001888-199809000-00020

- Zoller A, Hölle T, Wepler M, Radermacher P, Nussbaum BL. Development of a novel global rating scale for objective structured assessment of technical skills in an emergency medical simulation training. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):184. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02580-4

- Swanson DB, van der Vleuten CP. Assessment of clinical skills with standardized patients: state of the art revisited. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25 Suppl 1:S17-S25. doi:10.1080/10401334.2013.842916

- Boulet JR, McKinley DW, Whelan GP, Hambleton RK. Quality assurance methods for performance-based assessments. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2003;8(1):27-47. doi:10.1023/a:1022639521218

- Driskell JE, Salas E. Stress and Human Performance. Psychology Press; 2013.

- Lauria MJ, Gallo IA, Rush S, et al. Psychological skills to improve emergency care providers’ performance under stress. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(6):884-890.

Thank you for a very well researched and written article that brings home many known challenges and makes useful suggestions both for seasoned and novice instructors! Keep up the good quality work! /David

LikeLiked by 1 person