Welcome to our 12 Step Guide to Running a PCC Training Exercise at the unit level

Outline:

Introduction

Step 1: Decide the goal

Step 2: Decide outcome & objectives

Step 3: Decide scenario length

Step 4: Anticipate type of patient model and task trainers

Step 5: Select, train, and brief cadre

Step 6: Identify desired training locations

Step 7: Identify transportation

Step 8: Craft a believable and relevant operational situation brief

Step 9: Determine MOI and the patient script including trended vital signs

Step 10: Determine logistical requirements

Step 11: Execute. Execute. Execute. (With pearls and pitfalls)

Step 12: Debrief the team and provide feedback

Appendix A : Short, Limited Resource Example Scenario

Appendix B: Advanced, Lengthy BN Exercise Example

Introduction:

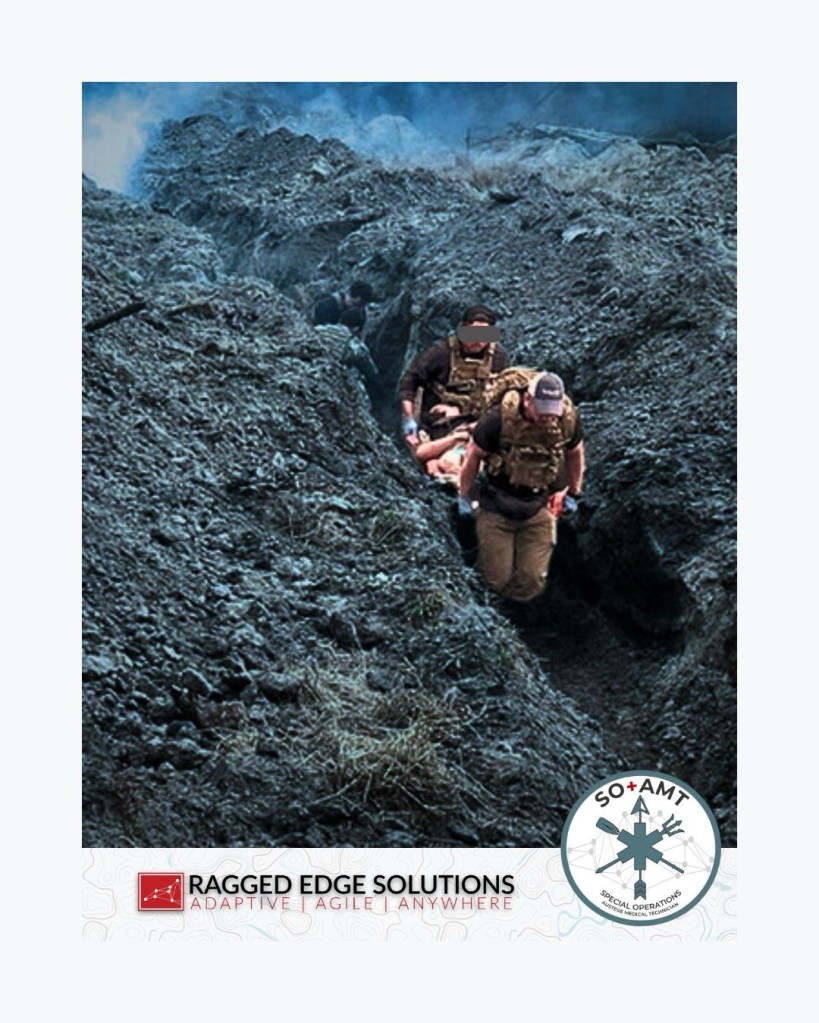

This article is meant to help senior medics and unit providers set up prolonged care training at their own unit, if they are unable to attend a contracted course or want to replicate a Ragged Edge style event at their home unit. Since 2014 we have trained thousands of people, over hundreds of prolonged care exercises, to include civilian, non-medic laypeople, up to clinicians at the highest levels all over the world. In that time we have found that certain elements can make or break a PCC training event. Running this once or twice a year is not too bad with the proper logistical support and enough lead time, but doing it dozens of times per year is extremely difficult and will burn out the most dedicated instructors and support staff. Sometimes a unit will have parts or most of this recipe but are lacking in certain aspects like moulage and trained role players. In those cases seeking outside help has helped many people maximize their existing training.

The most important part of this article is a brutal truth:

Most units are not ready for a prolonged casualty care exercise and could save more lives by spending those hours getting far better at TCCC instead.

Even if leadership says you need to prepare for Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO), you simply can not run a good marathon if you’re still doing poorly at your 2 mile. Simulated combat casualties will not survive for 5 hours if their first 15 minutes are sloppy, or if medics are not even allowed to do blood transfusions. However, If your unit is not just passing TCCC lanes, but knocking them out of the park consistently, then you can consider prolonged care training. Excelling in TCCC may look like:

- Tourniquets ALWAYS placed under 30 seconds, and remove the distal pulse every single time.

- Knowing all TCCC medication indications, doses and using them without error in scenarios using training vials. (No verbalization of meds)

- Critical interventions implemented properly, under time limits. (Excellent IV skills, seamless blood transfusions done at least quarterly.)

- Mastering all aspects covered in our TCCC training article

Prolonged care borrows concepts from many disciplines such as emergency medicine, critical care medicine, nursing and many others, which means a lot of advanced concepts and pathology going on. By the nature of the definition, combat casualties require timely evacuation to reduce mortality, but the operational environment and other factors prohibit it. It’s NOT a skillset designed to allow taking unnecessary risks by delaying evacuation, but a contingency to survive “Plan B” when better evacuation plans have failed, and while we troubleshoot getting patients to care earlier.

Let’s dive in.

Step 1: Decide the overall goal of the training event

It should be very clear to all involved as to what type of event this will be. A couple options are a formative/mentored learning event, or a graded validation scenario experience.

A learning event is a “hand-holding” event where you slow down to ensure everyone understands what is going on. If they remember the right medication and dose, then kudos and compliments. If they miss pathology, watch vitals spiral and push the wrong medication or dose then you can pause the scenario, socratically question them, then spoonfeed them the answer if they continue to draw blanks. Keep note of what they did poorly on to catch trends so you can improve the train up for the next exercise. If one team missed an intervention, they might not have studied or prepared well. If most teams did, then perhaps the train-up was inadequate.

A graded validation is meant for those already well-trained to receive a pass, fail or evaluation score in preparation for deployment. You could potentially use the same scenario for either type of event but could edit and optimize it depending on the desired goal. You can still have a minimal degree of socratic questioning if the validation exercise needs a little push, but it needs to be documented as a weakness for retrain during debrief. For example: “You caught that he was having an anaphylactic reaction. You didn’t know the right dose, or when to give more, and instead focused on Diphenhydramine. Therefore, I would like you to teach a class to the company medics and providers on anaphylaxis management next Tuesday morning.”

Catastrophic failure of a validation could result in a retest when available, if this is a validation lane. If not, retraining through other means will have to be explored by senior medical leadership. Have a fair and impartial plan for that ahead of time.

Ultimately, know your participants and their skill level and strive to instill good decision making with good medicine.

Step 2: Decide what the desired outcome and learning objectives will be

Reference the original critical task list by the PFC working group on ProlongedFieldCare.org and look at the new PCC Tier 3 Learning Objectives on Deployed Medicine for inspiration. If you know your unit’s mission essential task list (METL) and EFMB/E3B tasks, you can incorporate those into any additional collective tasks to help in getting buy-in from your leadership. (Now your PCC exercise is doing 3 things for your commander and is easier to get on the training calendar.)

Implementing PCC principles are important for every event. Other objectives may include exposing the team to certain situations such as complex patient care, forcing them to improvise medical equipment or change their care plan based on a scarcity of resources. As an example, If doing telemedicine is a required learning objective, the students must either be forced to do it, which will be somewhat detrimental to learning, or they can be placed in a complicated situation, beyond their scope of practice where they should strive to do this naturally, without prompting.

Didactic Training: While this article focuses mostly on the culminating exercise, you cannot expect medics to perform prolonged care without scheduling dedicated classroom training.

If you don’t know where to start with brand new medics, begin with a walk through of the new nursing checklist and PFC vitals sheet. Ensure they can fill it out when given an example of patient scenarios you write on a white board or projector. They should know “why” they are doing everything on the nursing list and what can happen to the patient if it’s neglected, or done poorly.

Afterwards, you can do a brief talk through of the pertinent CPGs and how a medic can read them to utilize for packing lists and patient care. Even the EFMB website has a list of pertinent CPGs a medic should read before attending, so it’s within reason you can expect medics to be familiar with these leading up to the exercise. The hard part of this is getting the attendance of all your medics for another few days on the training calendar for classroom before the lanes, and time for the lanes, as well.

This is a lot of information for your medics to learn, so it accentuates your hard work as a teacher by expecting them to study on their own; assign homework the weeks prior, expect pre-reading the night prior of every day, and even do pop quizzes orally or written to test them. The PFC exercise will show you who paid attention to the dose and frequency of Versed as their seizure patients SPO2 is plummeting. “92%…88%…84%…. 82%…78%”, while they struggle to flip through a resource they are unacquainted with.

If Doctors and PA’s study on their own to get better, then we can teach developing young junior medics to do the same. Not everyone will have the same motivation, but this will help some rise above and show you who might be ready for Combat Paramedic, IPAP or Medical School down the road. Expect more out of them and see who rises to the occasion. The PCC exercise will show who put in the work and who did not.

Taking a simple TCCC-type patient that had mistakes made and showing how that can impact them can be very eye opening and a powerful motivator. The objective of training should be to teach and evaluate, but mistakes that turn into bad days that can leave lasting impressions. What can be mitigated through understanding basic principles now turns into a difficult patient for doctors and surgeons to handle, much less a combat paramedic.

Examples of TCCC mistakes that can cause issues down the road:

- Poor Hemorrhage Control needing more units of blood, when it is a limited resource. Requires 2-3 more units of blood than a patient who had earlier HemCon. (Didn’t reassess junctional wrap, patient still bleeding during transport.)

- Any intervention not reassessed after movement could potentially not be working.

- Excess Ketamine/Fentanyl/Pain Management dose and speed pushed, accidental sedation, sonorous respirations, potential need for airway, laryngospasm, etc.

- Not padding an extremity during splinting, causing pressure ulcer and loss of limb function.

- Poor aseptic technique during procedures such as finger thoracostomy leading to sepsis.

- Ventilation complications from poor airway management (cric tube too deep and no ETCO2 monitor, or PEEP), delayed treatment, no suction causing issues down the road. Abysmal SPO2 if hesitation, or slow cric.

- Missed IV’s in training meaning delayed resuscitation, patient needing more blood, and waste of IO that could be needed later on.

- Reducing evisceration without irrigation and inspection for perforation, causing sepsis. Lack of reduction making hypothermia management more difficult or destroying tissue.

- Unnecessary Needle Decompression causing iatrogenic pneumothorax, hemothorax, respiratory issues.

- Needle/Finger/Tubal thoracostomy too inferior causing internal bleeding, requiring blood transfusions, etc.

- Hypotension, Hypoxia doubling mortality in Head Injury; LR worsening outcome due to hypotonicity.

- Giving hypotension inducing drugs when patient has low BP (especially head injuries)

- Loss of head injury evaluation trends for hours if using Versed

- Compartment Syndrome from TQ too loose for prolonged period.

- Excessive/insufficient fluid given to burns due to poor calculations.

- Delayed TQ conversion causing more ischemia, more pain management, etc.

This list is not all inclusive, but just some of the examples we have seen. You have to watch your students and pay attention to what they do, the corners they cut under duress, and how long it takes them. If you are unsure how a mistake in a procedure may impact patient, reach out to the senior medical advisor assigned to the exercise for help. If you see no way to implement mistake into scenario, then include in debrief.

You don’t want to overreact to minor details, “You didn’t do this small thing, so now your patient went from a BP of 120/80 to 80/50.” However, you can still drive the point home that high attention to detail is important. Sometimes small nursing errors really do cause permanent injury and death down the road.

Step 3: Decide the length of the scenario

This is where you train to time instead of a standard. They need to make mistakes and live with the consequences of their actions or inaction to let those lessons really sink in. Are you trying to replicate your anticipated, worst-case scenario for an upcoming deployment, or train for a specific amount of time to facilitate specific learning objectives?

If your team has absolutely zero PFC training, then it may be worth a simple 3-4 hour mini exposure lane to get them used to the nursing checklist and some of the care before throwing them into a 12-24 hour onslaught. Even an 8 hour lane for a new medic and grader(s) can be mentally draining.

If your team has already started to implement solid trauma lanes that start extending past an hour, you can more easily consider longer lanes. But how long..12, 24, 48 hours?

Learning objectives can be packed into a short time but may not allow the monotony of a very prolonged care scenario to develop and give participants the chance to implement nursing care. A team performing PFC for shorter than 12 hours will seldomly implement a rest cycle while a small team caring for a patient over 24 hours may have decreasing returns on other learning objectives. Participants that have never been to a 24-hour plus exercise or training event won’t understand some of the concepts needed from an 8 hour event.

Most soldiers and sailors have had to do 24-hour ops at some point in their life, so this is possible if there is adequate support. Pick your poison. Does the length support the objectives? Shorter scenarios can have explicit and limited goals such as perfecting team dynamics while layering on an interesting but shorter scenario. “Time warps” are possible to demonstrate advancing pathophysiology (Sepsis, ARDS) but we have also found other creative ways that don’t involve distracting the team with an artificial time warp. Injecting a new patient into the scenario is a great way to freshen up the team. This can be as simple as a local national who arrives at the aid station with an old, infected wound, or a partner force relative… whatever works with the Medical rules of engagement and training objectives. Be careful with reasoning of why they need to treat this new patient as sometimes medics may attempt to get out of treating the new patient with excuses. You are focused on evaluating them, while they are focused on a scenario and could be trying to conserve resources because they don’t understand the value in taking care of this new individual.

A newer method that I have been playing around with is the secondary hit as explained by a Ukrainian surgeon at a conference in Estonia: The Ukrainian unit that he was supporting crossed a river at night to attack an enemy position. They sustained casualties and the counterattack did not permit them to evacuate casualties back for over 12 hours due to effective enemy indirect fire and FPV drone harassment. When they finally exfiltrated back across the river with the 12+ hour old casualties, they were attacked in their boats before arriving at shore. The surgeon described a rolling mass casualty event that arrived in waves with casualties having old wounds, or new wounds or both at the same time. Multiple casualties not arriving at the same time adds more stress, but unfortunately requires you to have additional roleplayers. Sometimes real life is crazier than anything we can imagine.

If the worst-case scenario identified during planning will be 24 hours or more, the best validation scenarios will match that and this truly lets your medics experience some of the “boring” down times, nursing care and having to transition from a TCCC to PFC mentality. Down time is difficult because TCCC lanes are usually fast paced but it can be difficult to step away from the patient and not be doing an intervention. Scenarios this long can also include forced work/rest cycles with “wake up” criteria. If you don’t schedule a mandatory time to make your medic step away from the patient, they may just power through and never want to leave. This doesn’t allow you to assess their ability to brief the team on when to get them.

If you throw your medics straight into a long 24-36 hour brutal medicine fest without tons of prior training and exposure then you will have to do far more hand holding with some concepts. They may also retain less due to being tired and overloading bandwidth. This means when you make the patient exhibit certain signs/symptoms, your medics may not catch on and may need more breadcrumbs tossed their way, unlike a TCCC lane where they should already know. Your Instructors and other support staff will also have to attempt to remain vigilant during this time, which is a big ask and lots of bandwidth for them, as well.

You can still get plenty of utilization and instruction out of an ~8-12 hour lane. The TCCC portion should be done in under 30-45 minutes, then they get a few hours to handle some critical issues, do nursing care, set work-rest cycles, and call telemedicine and do a patient handoff. This is probably the max time frame used if Manikin is all you are able to acquire, as longer durations don’t provide much feedback, don’t have medic buy in, and the proctor is working a lot harder to pretend to be cadre and patient. Another advantage of ~8-10 hour lanes is you can run them in one day, which means the next day you could do more lanes if you have that many teams in Company/BN to be validated. However, you risk medics communicating and giving away “answers” the next day, so be cautious and consider altering scenarios if doing two days in a row. You could even alter the scenario for the second day so that someone given the “answers” would be providing inaccurate or harmful care due to a change in severity or indication.

Minimally, you can do a super basic intro to PFC principles and nursing care checklists and simple scenarios in 3-5 hours. We provide an example of this in a later section. This may be an initial exposure to an event, or even extending the last trauma lane of their TCCC training by an hour or two if they don’t need to do another run due to failures, or weak lanes. If it’s a matter of getting off at 1pm on Friday or getting another hour of training in, this may be an easy win.

Step 4: Anticipate what type of patient model and task trainers that you will have access to.

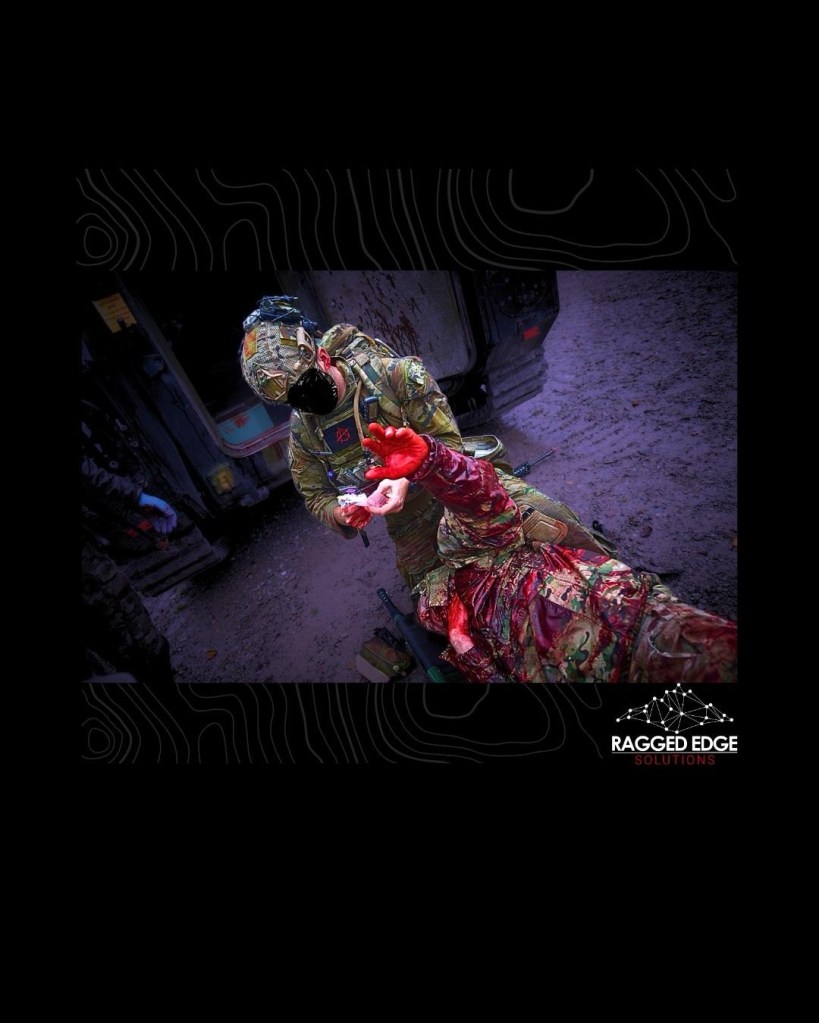

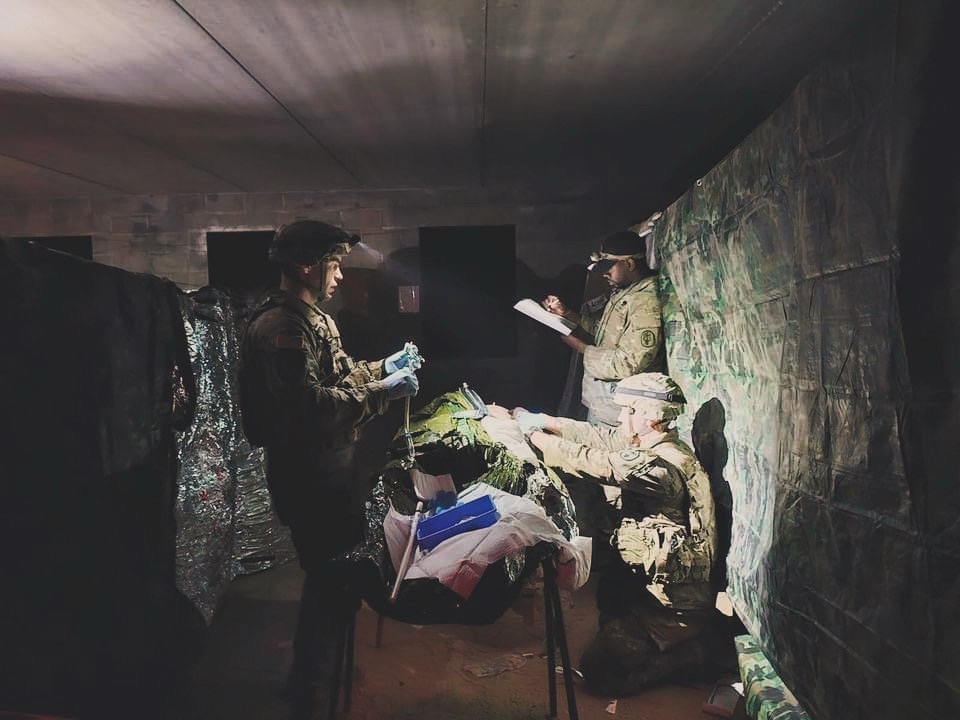

Utilizing an actor/role player with high fidelity moulage and integrated task trainers seems to work the best for the majority of situations… but not all. In initial PFC training, during the classroom/walk-phase, a manikin can be a useful training adjunct. If you have a high or low fidelity manikins, either can work over a longer period of time, but the realism is greatly diminished over a trained role player providing real-time feedback. No emotional connection is established to be leveraged, screams by the cadre speaking for a manikin fall flat, and teams lose interest quickly over the length of a full mission profile lane. Task trainers (devices you perform a procedure on) should be available to each team so that when the indications for a certain procedure are presented and the decision to do a procedure is made, only then does the proctor reveal the task trainer. Doing so too early will clue in the participant as to the proper procedure without them thinking through the problem. If they see the roleplayer wearing a cric trainer or thoracostomy trainer, or your IO trainer is exposed, it might be a dead giveaway. You want them to have the freedom to make decisions and mistakes.

If utilizing “volunteers” you probably have to put in a request for support 2-3+ months out through your battalion for roleplayers for each lane you are running. This could be one lane per medic/team/platoon. The more medics per lane, the less value. The more lanes, the more support needed to run them. This may be easier if your unit leadership is able to agree to put roleplayers in for Army Achievement Medals or other recognition for being actors that get poked, prodded and uncomfortable for 24+ hours. By volunteering and providing high quality instruction to the medics, we firmly believe the value added is more than worth treating a plastic manikin.

What about perfused cadavers, expensive manikins and other “high fidelity” mediums besides roleplayer and manikins? Those may not work well for the full 24 hours. Some high fidelity patients may provide certain interventions better than a roleplayer, however. One thing you can do is have two patients initially, or a second patient that arrives but does not continue on for the full exercise (local national goes on to their hospital, patient expires, etc.) This however adds more moving pieces and makes it more difficult to run, therefore I don’t recommend attempting two patients/mediums until you have successfully done a good 8-12+ hour lane with just one roleplayer and your medics got a lot out of it. If you do end up running a manikin/cadaver/other medium with your live roleplayer, the roleplayer scenario can be less critical during certain windows to maximize the limited opportunity with the other medium. For example, while patient “A” needs his airway taken soon, Patient “B” is probably not developing hypotension, (unless you have advanced students). It may be easier to incorporate that high fidelity medium into TCCC training or PFC classroom train-up to build up for the main event.

Step 5: Select, train, and brief cadre

The most important piece in a PFC exercise is the Instructor for each individual lane. An articulate instructor can provide invaluable experience to medics on the lane, even if this is done in a tent on a stuffed animal behind the company. There is no amount of high quality moulage, supply or support that can make up for the difference between a novice instructor compared to an amazing one. At the end of the day, it is about how good the lane proctor is at guiding the group through a scenario and imparting knowledge.

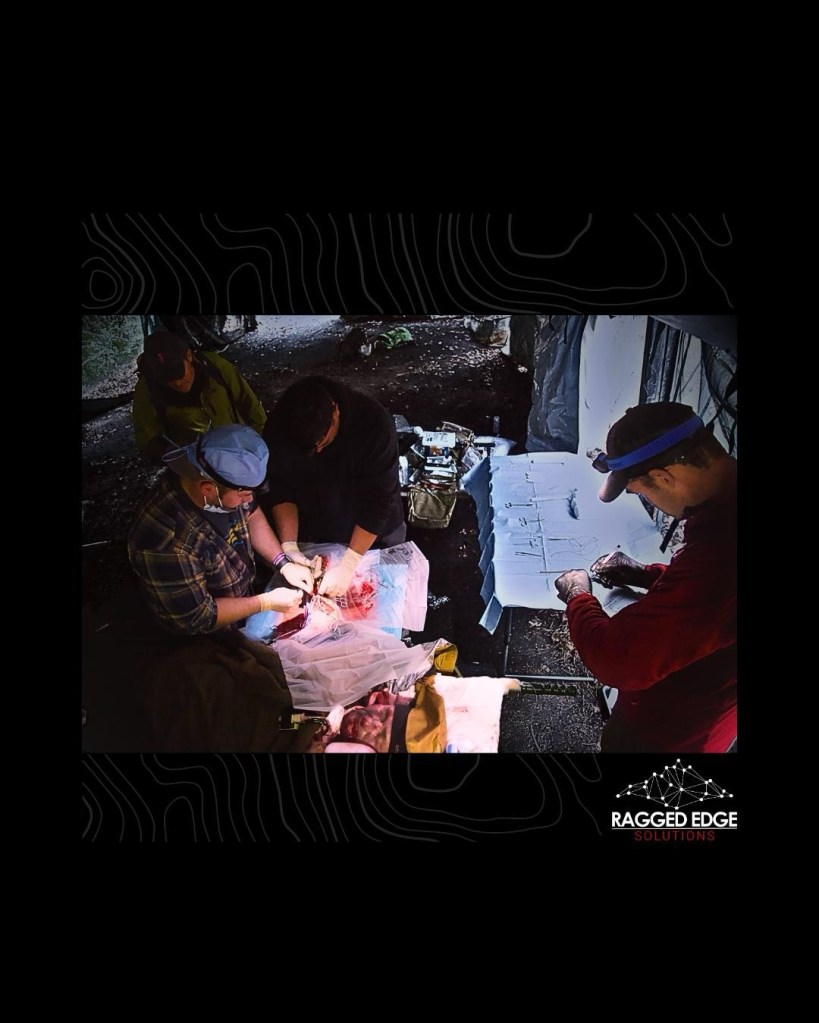

You need 1 competent senior medic or PA per lane, and then 1-2 of the most senior and experienced to float around as quality control, and acting Telemedicine to help the lanes run smoothly. Therefore, you likely must request guest instructors from other BN/BDE to help you make a PFC lane. These may be PA’s, Doctors and other senior providers (Senior Combat Paramedic/SOCM/18D) which bring most of the value to a PFC exercise by bringing some of the critical care experience and/or prior PFC exercise experience to the lane.

One BN PA can probably not run multiple simultaneous lanes of a lengthy exercise by himself for all the medics in his unit, and if he could it would be because each lane has a stud senior medic on it. A BN PA by himself could easily run a shorter BAS exercise for one small group at a time, as we provided in Appendix A below.

The more “switched on” your instructors, the more juice you get out of your exercises. This may mean reaching out to other units even outside your BDE, such as SOF medics, Emergency Medicine PA’s and Doctors who have done other PFC exercises. You can even bring in experts from the hospitals on base, such as Burn Doctors or CRNA to give respective ~1-2 hour classes during the multi-day classroom preparation or the exercise. Everything you teach them, or expect them to self study is fair game to incorporate into the scenario.

Cadre should be well versed in the operational environment being simulated AND several medical specialties. Either that, or a team of experienced clinicians and master tacticians should be paired so that good medicine does not come at the cost of bad tactics. Proctors should be intimately familiar with the scope of practice of the level of medic and learn that of the particular medic so that they can teach, train, and mentor to a level appropriate for the desired outcome. They also must be read-in to the type of event this will be. A validation should NOT contain administrative pauses for lectures and coaching. Conversely, an experiential, mentored lane should not be run by a stonewall grader who is expecting flawless critical care from a novice graduate.

When you’re close to running the exercise, you should get the proctors together to brief the scenario so everyone is on the same page with learning objectives. Consider the morning of the exercise if the Cadre know the students well. More than a day or two prior is also a possibility if there is a zero chance of them leaking the “answers” to acquaintances in the unit being graded. People naturally want to help their buddies look good, especially if this is more of a validation exercise than strictly learning.

The briefing ensures a more standard experience as a medic is expected to handle a certain issue the same. You may have a new proctor running a lane who may not understand a certain pathology, intervention, or is outdated, so now is the time to ensure everyone is on the same sheet of music. You don’t want one medic getting chewed out for not considering mannitol and the other getting chewed out for considering it, then a third told medics they shouldn’t use it anyway. Remember, this is about learning objectives. For example, you may make a list similar to the following:

- Expertly manage a patient in TCCC (Grade harshly)

- Initiate a Whole Blood Transfusion under xx minutes, completion by xx to xx minutes.

- Successfully use entire Nursing Checklist, consistently

- Show familiarization with ____ & _____ CPGs

- Medic Briefs Team on Wake-Up criteria and other PFC Principles

- Evaluate Chest Tube ICTL

- Evaluate Cricothyroidotomy ICTL

- Evaluate pain management (Ongoing)

- Evaluate Medical Math (Drips, Burn Calcs)

- Evaluate TBI management

However, PFC scenarios are dynamic and the participant gets a vote. For example, lets say your head injury patient goes into a seizure. A medic who did not study the CPGs or cannot quickly reference them and may fumble for 20 minutes, or go down a different rabbit hole. One may have to take a long time look up the medication, one may give Versed but at the wrong dose, and another may wait for IV access instead of giving IM, and another may be surprised their one dose didn’t work and not know how often to redose. A good proctor must account for all of these to develop medics at their different stages. This is also why a wandering senior PA/Doctor is essential as they can help a proctor manage unforeseen curveballs.

Therefore, your instructors should initially step back and let the students attempt to figure it out and not be spoonfed instantly. Tell your Cadre to ask socratic questions to get the student to an answer.

“What does this patient need? …. Well, which vitals are not good? … What do you think could be causing that? …. So we should consider which intervention first?”

Then, they can slowly walk the dog giving more and more hints until they need help and eventually be spoonfed. Cadre should be documenting what they knew with no prompts, some prompts, or had to be walked through. This shows areas for improvement and trends for future exercises. While all medics may find their way to the answer, some may have done it better than others and that should be recognized.

Just like TCCC, these errors may lead to patient death if the student takes too long to recognize the issues or causes further harm. We recommend a student that makes a fatal mistake during PFC, such as on hour 16 of 24 not stop the lane entirely. The Instructor should pull the medic aside, debrief them on what went wrong, then restart the scenario to right before the incident and continue. This ensures they still get the value of the exercise that took months to set up, and they can learn a valuable lesson. You need to exercise caution with patient death in scenarios. It should never, ever be the focus of a scenario, just like in TCCC. However, if you want to grade them on their ability to handle a non-traumatic arrest later on to ACLS standard, Capnography, H’s and T’s, then that can be incorporated as one of many learning objectives. It should be explained to medic that was part of the evaluation, and not “just dying to show you that some patients die.” That is not a real objective, and not a good use of training time. Additionally, you can incorporate ROSC for them to practice managing that and to get a “win”, as well.

Step 6: Identify desired training locations

Locations should closely match the scenario being prepared for to increase participant buy-in. At minimum, This could all take place at a single location utilizing a parking lot, a tent or a team room though some fidelity could be lost. If ideal locations cannot be integrated, let the participants know of the limitations up front. Many PFC events have taken place in old condemned team rooms, CONEXs, or even garages and sheds. Other widely available-resources such as airborne mock trainers, static personnel carriers, and other vehicles should be implemented. If utilizing military training areas you will also have to put in a range packet for the area(s) you will be using far in advance, and ensure someone shows up to the brief for it. While you can run an introductory lane in a static area for ~8-12 hours, when pushing beyond 18+ hours it may benefit for them to have multiple movements, locations and vehicle platforms. MOUT sites can also work for this because you can fit 3-4+ teams in different areas within walking distance of various support Cadre.

The teams should be close enough together to walk to the different lanes/clinics, but not hear what is going on with other platoons, or communicate answers. The convenience helps ensure that the senior medics/providers can easily watch one lane perform the planned event at ~1600, then walk over to see how the next lane handles it at ~1620. When one lane is addressing the designated event, the other lanes are doing nursing care, planning and trending vitals.

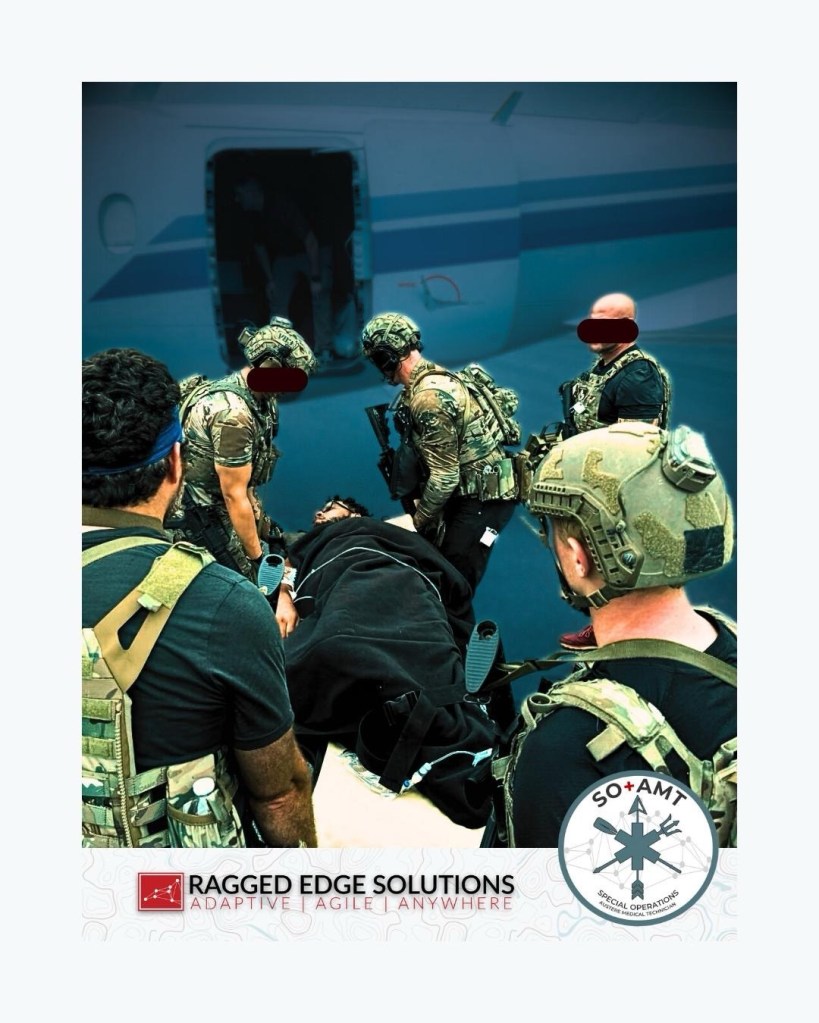

Step 7: Identify the type of transportation that you will be utilizing

Transporting a patient from the “X” until the end of the exercise: Movement means vehicles. You are only limited by your creativity, initiative and safety of the patient(s) and medic(s). You can make a lane that begins with TCCC on foot, multiple security halts moving back to one vehicle, then a dismounted movement to another (ATV, Civilian Truck, MRAP), then taking that to a field hospital, another foot movement/vehicle from guerrilla hospital, then movement using another platform to additional spots, hospitals or even boats, helicopters and fixed wing. Your creativity, and units METL can help drive this to add the stress and difficulty of evaluating and treating a patient during loud, cramped vehicles in bumpy terrain.

Ensure to have multiple backup plans before starting, because vehicles can break or weather can prevent helicopters on the day you launch the exercise. You must still provide good training value regardless if you only end up with one vehicle or must do a full 24 hours static in a MOUT village. Part of this learning is practicing medicine in confined or uncomfortable positions, as well as during movement where talking and assessments/treatments are more difficult. However, if these all fail you could still run a static PFC lane after the TCCC movement, as medicine is the most important part of the exercise. In fact, if this is your units first small PFC exercise, this is an easy way to dip the toes in and keep it manageable.

Remember to emphasize safety and drivers not driving crazy to add stress; More stress can be added by driving slower in rough terrain than trying to take turns fast on paved roads. This is arguably the most dangerous part of the exercise and drivers should be briefed that way. Generally speaking, increasing the type of conveyances utilized will challenge a team, and give them more reps on different vehicles, watercraft or aircraft but decrease time for patient care. Weather has also severely affected many PFC lanes on or near the water. Air conditioned/heated vans have stood the test of time and adequately achieve training objectives of many different types of transportation; your unit may have some assigned, or you may be able to have rental(s) as part of the exercise. It also enables medic and proctor to easily speak to drivers for scenario management. This is in contrast to an LMTV, where a proctor in the back will need a radio to talk to the TC in the event driving is unsafe or a change is needed.

Step 8: Craft a believable and relevant operational situation brief

Knowing all the aforementioned information combined with your anticipated area of operations while deployed will then allow you to write an operational situation that contributes to the realism instead of losing the students before you start during the pre-scenario mission brief. This is also a good time to decide the depth of the operational and tactical scenario and how much you want that to influence the medicine or, conversely, how much do you want the medicine to influence the tactical situation.

This is also a chance for medics to get exposed to some medical planning to see everything that goes on at higher levels. Bringing in some Senior NCO’s or Officers for a portion of the brief may help this feel more real for the junior enlisted and young NCO’s.

Step 9: “The Patient” : Determine Mechanism of Injury (MOI) and the patient script including trended vital signs

You can now take all of that and decide on an MOI that will be believable enough to get off the ground, evaluate initial lifesaving TCCC and then smoothly (or not so smoothly) transition from Tactical Field Care (TFC) and Tactical Evacuation Care (TEC) into prolonged field care. Does the team have a RAD 57 device that will display SPCO, SPMET as well as SPO2? The participants need realistic moulage and vitals signs that push them to perform the specific medical tasks being evaluated. Are your cadre ready to give realistic values with those devices? What if they have an iStat or Epoc? Cadre must be prepared to play off what the students may do such as giving a certain medication that affects vital signs, or whether or not they administer appropriate resuscitation fluids. Some students may have devices such as lactate monitors or an Emma Capnograph that measures end tidal CO2 in kPa instead of mmHg. Know what medics have and what you want them to have.

Similar to our TCCC article, you should include concepts in lanes your medics should already have been taught. Throwing them concepts they haven’t been exposed to means more work on lane instructors.

However, unlike culminating TCCC training, PFC training can have a little more hand holding. You want guys to master TCCC before attempting PFC, but they will likely not have mastered PFC concepts (critical care + nursing) before your 8-24 hour exercise, even if Combat Paramedic or SOF.

Once you know where your medics are at, and what you need to teach them, including assigned homework, you can design your scenario(s). We recommend looking through the JTS CPGs and seeing which 2-3 can be combined to create different patient evolutions throughout the time frame of your goal.

First, make a realistic TCCC patient, because the most important part of this exercise is them crushing the initial patient encounter. Then, you have time for some of the PCC issues to slowly trickle in and stagger. For TCCC we wanted to avoid too many injuries and issues to avoid being overwhelming. However, more injuries in a PFC isn’t as overwhelming because you can space the events they become applicable apart. Instead of everything needing to be done at once, every 45 minutes to hour or so, the PFC patient can have a mild, moderate or severe complication that stems from the initial wound set, and follow on care.

Patient scripting considerations:

- Be cautious with tension pneumothorax from penetrating trauma, or from a blunt trauma such as a rollover. They are realistic, but the prognosis is poor without surgery. If you want to test them on tension pneumothorax and needle/finger/tubal thoracostomy, consider it as a complication of BVM/ventilator use down the road and less as an initial TCCC injury.

- Facial trauma and facial burns are not the only reason to take an airway, but it can become the “easy button” for medics. Consider other reasons so they can practice “when” to make that decision when it isn’t obvious. Tier 4 (NRP/SOCM) students may have blast lung or another etiology (TRALI, ARDS) that requires ventilation and therefore taking airway to provide that ventilation. This may also distract them and result in bilateral thoracostomies instead of addressing ventilation if they aren’t recognizing pathology.

Varying degrees of Burns, Head Injury, Crush, Compartment Syndrome, Airway and Ventilation issues, Resuscitation and more are all complex concepts you can use to have a medic learn to assess patients and continue nursing. Some of these can be advanced to challenge Combat Paramedics, SOCMs and new providers, as well. At minimum, a medic should be exposed to these concepts and know where to reference these in order to apply it during the exercise. This may be printed or digital guides depending on if electronics are allowed during your exercise(s).

Then you are reverse engineering a patient and MOI that can produce the desired concepts and wounds you want to test them on. It doesn’t take much to consider blasts, IEDs, crashes or rollovers causing burns, fractures, head injuries and thoracic trauma that give you 24+ hours of work easily. Avoid farfetched scenarios such as “IED, and then got bitten by a snake.”

Once you’ve decided what you test them on, and how many lanes you are running, you need to create a trending vitals sheet with your scenario playbook. This is one of the other most important pieces because a well designed scenario allows the lane proctors to deliver high quality scenarios even if they are novice. It takes rhe guessing out of it, especially if senior PA/Doctor is available for any curveballs your medics may make that a novice instructor can’t handle.

This playbook allows your proctor(s) and yourself to slowly take your medic from the last issue to the next. For instance, maybe at 1800 they recognize the patient needs an airway due to ventilation issues. You would have the medic solve that issue, then the senior medic/PA would walk ~100-200m to the next lane where they would have then have the next medic handle the same part of the scenario. This ensures all lanes are launched and kept within 20-30 minutes. Which gives you the ability to have “events” scheduled in the patient every ~60-120 minutes depending on overall length.

If you are running just one lane, it’s easier to keep the scenario flowing, but the provider to patient ratio will be stretched and the students may get less value.

How to brief and run the roleplayer:

Check in with primary and alternates and their supervisor in weeks leading up to the event to ensure it’s not forgotten about.

Ensure they are tracking what the event will entail and what to bring.

In addition to the normal TCCC patient briefing you should have already read, you also need safe-words and break words for the roleplayer. You can also talk to the roleplayer with writing notes on a phone/paper notepad and showing them, or bluetooth earbuds.

We recommend whatever method of communication you use does not become predictable. The student will start to take Instructor communication with the patient as an opportunity to check for a change. Therefore, instructors should sometimes communicate with patients when interventions are not needed, when they are done well, even to give a follow-on signal for when the action should start later on.

“When you see me do ______, start your seizure.”

“Wait 5 minutes, then start dry heaving”

“When the vehicle arrives, start screaming in pain when they move you to load you up. Do not stop until I squeeze your foot”

“Are you doing okay? Do you need anything? (Checks in on roleplayer while having the situation not change for the medic.)

Between “events” on the 12-24 hour schedule, the roleplayer can check in with Instructor to administratively sit up, go use the restroom, eat a snack outside of the scenario and then come back.

The proctor should help the medic set the roleplayer up for a break, remembering to disconnect any pertinent tubes or wires needed for mobility and to shut off IV lines. If the patient is not contraindicated to receiving oral fluid, the roleplayer can also ask the team for water during scenarios. After all, part of the experience is nursing care to keep a patient comfortable. This means hydrated, padded, rotated and everything on the nursing checklist.

When roleplayer returns from a 15-20 minute break nearby, it is the medics responsibility to ensure all interventions are still satisfactorily implemented when the scenario is ready to begin again. While this is an administrative out of scenario movement that can interfere with the medical interventions, the applicability to real patients and medicine is that patients may dislodge interventions during movement and need frequent reassessment. Medics are responsible to fix any issues, such as IV catheters that came out and need to be replaced.

For more roleplayer cues, read our TCCC Training guide.

10: Determine logistical requirements

Knowing the desired learning objectives, time available, training areas, vehicles, type of patient(s) and operational environment being simulated will finally allow you to build a minimum packing list and the supplemental equipment required to support the scenario. If a team is simply utilizing their own equipment organically available, without supplemental equipment, realize that some learning objectives may not be met. If they don’t have a ventilator, they won’t be performing ventilator management. You want them to primarily train on what they will have. However, if they don’t deploy with a monitor then EKGS for certain scenarios may be difficult to provide. You may have to decide between what learning objectives you want versus how applicable you want the scenario. If they don’t deploy with a monitor, but you want them to have a bad EKG, do you show them the patients EKG, or incorporate a local national hospital that has one available but no providers to assist the team? This is for you to decide what to focus on.

Follow up early and often: This is a lot of moving pieces that require being checked in on 1-2x a week to ensure they don’t fall through the cracks. The week leading up to the exercise and day prior should also have extra caution and accountability to align moving parts.

Training Setup Checklist:

- Primary and Alternate Roleplayers named and scheduled

- Guest Instructor(s) Scheduled

- Telemedicine/Surgeon Scheduled

- Range Packet(s) submitted, Alternate Location

- Vehicle(s) booked, and Alternates chosen

- Food (MRE + DFAC delivery), Water, and Supplies checked

- Schedule & teach didactic training with mandatory medic attendance (~ 1-3 days)

- Radio PACE plan for telemedicine

- Double check above list early and often

Step 11: Execute. Execute. Execute.

Everything must come together harmoniously, transparent to the student to keep them immersed in the medical and operational problem set. The cadre must be able to let the participants run with the medical problem and not intervene too much. Things will go wrong so being flexible with the solid bones of a plan will keep everyone working toward the same goal. This is why learning objectives are so important, because if something happens last minute that takes a piece out of play, you still have other tasks to train the students on. If primary and alternate equipment breaks, your minimum value can still be a PA/MD doing low fidelity walk-through on a concept.

Pearls & Pitfalls of PFC training:

- The “Time” Warp: As mentioned above, this isn’t as realistic as inroducing a second patient that has this condition going on in an appropriate timeline. However, this may be a consideration if your lane is not long enough to factor in longer term conditions. For example, if you wanted to test your medics on sepsis but only have 8 hours, then you may have to start that section of the scenario with walking up to the litter, and saying “For this next part, we will assume that xx hours have passed. You notice that these are your new signs, symptoms and vitals.” This allows the medic to frame the pathology in a time frame, because giving sepsis a couple hours after an injury is unlikely and as fake as making a tension pneumothorax 2 minutes after being shot. This fast forward tool also enables you to keep 3-5 different lanes on the same time schedule because the senior provider rotating through lanes can be present for the more difficult events tailored into the scenario.

- Forced Work-Rest Cycle: If you do not FORCE a work-rest cycle or two into your scenarios, your medic(s) will probably be so obsessed with keeping your patient alive that he won’t want to take a break or leave the side of the patient for the entire 24-36 hours. We have witnessed this multiple times. This unfortunately means that the medic doesn’t get trained on his ability to brief his team on how to handle the patient while he is gone, and what criteria to come to “wake him up.” (Or grab him from wherever you separate the medic.) Ensure you say “At this time in the scenario we are pulling the medic away for a designated rest cycle to test the non-medics ability to take care of patient(s), in case the medic needed to nap, or go use Telemed in another building. Brief your team on what to do and when to come wake you up then step out to the rest point. This gives non-medics and leadership (if non-medical unit) an opportunity to plan shifts and take care of patients.

- Back up plans for Backup plans: You will plan more moving pieces than a typical TCCC lane for this. More vehicles, more advanced and higher ranking instructors, and even the weather cooperating. Ensure during the planning process you go down the list and go “What if this instructor cancels? Who else can we bring? What if this vehicle breaks, where are they for those 4 hours? What if the helicopters can’t pick them up?” I have had to be incredibly resourceful and jump through hoops 48 hours before launch to provide a great experience for my BN. Expect to follow up and confirm often with all pieces to ensure you still get an 80% solution. A great lane proctor can still provide a lot of value talking to a medic through advanced care for 8-12+ hours in a tent in the middle of nowhere, regardless of what else happens.

- Being fresh matters: I notice more platoons/teams are successful if they have both had TCCC recently (~30 days), and even more so if senior Medic/PA/Company Ops designates mandatory time on calendar for medics to go over PFC training with their unit. This may be as simple as a nursing checklist and talking through what it will look like so everyone knows their roles. The longer it has been since TCCC or medical training has been incorporated, the bigger risk the medic and team may not be as spun up on their skills. This lowers the value of the training opportunity by playing catch up.

- Stagger the start times close together: The initial limitation is TCCC, which shouldn’t take as long initially besides 10-15 minutes, reset “x” and have the next lane ready to go. Try to have the lanes start as fast as possible to keep all the lanes close. More than 30-45 minutes is too long, and an hour means your first and last lane could be 3-4+ hours apart. It’s miserable, slow and hard to track. The senior medic should watch the initial part of all lanes for TCCC failures, then let the lane instructor themselves take to the next step watching blood transfusions as senior medic resets the lane and next patient.

- Tracking fluid: Some scenarios require the patient to receive a lot of fluid, such as burns, crush syndrome, etc., IV pain management and more. Medics should truly be calculating ins and outs. If you are using a roleplayer, proctor should track how much fluid the roleplayer is getting. After 1L, fluid should be administratively moved to TKO and only given verbally, besides the rare normal saline push to represent a medication. Additional bags being hung probably aren’t high value training since it’s just spiking a bag. Med math can still be calculated, Urine outputs given, and drip rates can be demonstrated then dialed back by proctor. Additional bags of NS/LR/HTS/Blood can be handed to proctor so they are gone from medics supplies but not overflowing roleplayer, or wasting limited supplies pouring out on a manikin arm.

- “I forgot to pack that medication…”: Optimally, a medic shows up with all the vials, medication and supplies they need. However, this can quickly turn into ruining the training value of the entire lane when they realize they don’t have a critical medication or two, such as Versed, Epinephrine or similar. This may be a medics first time considering more meds than an aid bag can carry and that they are comfortable with. You can definitely choose to let them ride with what they have the entire time, or even have the patient expire as a learning point, then bring the patient back after a quick debrief and give them the medication they need. However, it may be a consideration for the instructor to note that they forgot the medication, but give them a chance at redemption by asking, “if you had it, how would you give it and how much?” After all, during a lengthy PCC exercise we are helping them learn through this exercise and not necessarily expecting them to be critical care masters. This way they still get penalized during debrief so it hits home that they failed to pack the critical med, but if they had it, that they still performed well. Failure to pack the medication AND then not knowing how to use it is even more detrimental and may require a remedial class they can teach the BN on that pathology and medication.

- Throttle and Brakes: Part of PFC and other training is knowing when to dial back, or when to add more stress and complexity. Have plans and methods discussed with instructors in order to make the scenario applicable for both the E-2 new AIT graduate, the E-6 deployed combat paramedic and everyone else. We may have to teach those at different levels, so try to plan for flexibility. We don’t want to overwhelm a stressed private with the oxygen-hemoglobin disassociation curve when the BVM comes out, and we don’t want a bored NCO or provider who is getting softballs. This is once again an area where the senior provider/NCO floating between lanes can help increase training value.

- 2 is 1, 1 is none: Medics should preferably get 2 IV lines in the patient, not just IO. One consideration is 1 or 2 upper extremity wounds so they can’t just do bilateral AC sticks. This may be an opportunity to consider External Jugular (EJ) sticks in the neck. This is partially to account for a sick patient needing multiple lines, and also an opportunity for more stick practice, especially in less easy positions. Additionally, roleplayers can’t receive their blood transfusions back through a fake IO trainer, so they will need a genuine line. It would be unfortunate if they used their 1 IO device on this patient and received more patients later…

- Bag Valve Mask: BVM use, and eventually Ventilator use is a skill even NRP and SOCM’s struggle with, and can cause lots of harm to the patient. They tend to bag too frequent and with too much tidal volume, so watch out for that. Non-medics may get caught up in adrenaline and stop bagging for 2-3+ minutes. However, bagging for a full 8+ hours without a ventilator may not be the highest yield concept. Only a few minutes may not make them appreciate the gravity of the situation, either. Therefore, it is up to you to consider how long in the scenario you want the team to bag. We recommend long enough that they realize how hard it is to do well for long periods without being detrimental to the experience. For example, after 1 hour and 10 shifts of ~6 minutes, they either have access to a ventilator or you can make the call to administratively stop, or develop a scenario in which patient starts being able to breathe adequately after response to Tx, Resuscitation, etc.

- Printed images of results: We recommend Cadre consider high quality printouts of not just pertinent exams but others medics may use. For example, if you are testing them on EFAST, instead of saying “you see fluid” you can either say “as is” (scenario matches roleplayer) or hand them a positive or negative EFAST view(s) with no prompts. Therefore it’s truly up to them. This can be done with HEENT exams (pictures of perforated eardrums, hemotympanum, pupils), capnography, or other situations. Pictures of urine color in a foley or dipstick results also work (if you can’t discreetly put food coloring or soda in the roleplayers catheter bag.) Keep the photos hidden, just like procedure trainers; if they see it, they will be thinking about it.

- National Guard: We hear your cries from the back. You have a MUTA4 homestation drill and no supplies or roleplayers. When you have annual training, you’re attached to an infantry battalion and Table 12 takes precedence, so you’re stuck providing range support. So what about us? Planning is your best friend. Approaching the command team with a good idea does not pave the way to great training, but having a well developed plan goes a long way towards command buy-in. The Medical Simulation Training Centers (MSTC) have all the resources, high fidelity manikins, and real estate you need. There are 11 National Guard run MSTC sites spread regionally that can provide the means to conduct PFC lanes. Units simply need to reach out to the MSTC course coordinator/ manager so they can best figure out what type of support can be provided. As mentioned above, also incorporate units METL tasks and E3B tasks into justification, too.

12: Debrief the team and provide feedback

After action reviews and intermittent debriefs are an important part of the learning process. During prolonged field care exercises that are supposed to be formative in nature, waiting until the end of a very long 24 – 48 scenario to do a single lengthy AAR will be detrimental to this process. Not only are guys exhausted at this juncture, but it was so long ago they may not have understood why they chose to push a certain medication. Shorter ~4-8 hour lanes may be easier to debrief at the end. However, if it’s a new team doing PFC for the first time, you may need to do it more often to maintain training value.

Think about breaking it down into phases. If the exercise is supposed to be a validation for experienced medics, with minimal injects by Cadre, waiting until the end to talk through the process may still have to be the method. You can utilize the PFC rubric to provide feedback on each of the PFC principles and capabilities throughout the lane.

Once the lane is over, a medic should be somewhat aware of how they did. This is because a PFC lane tends to give more on the spot verbal feedback. Unlike a TCCC lane, where we should expect a medic to perform well, most medics and even SOCMs are not prepared for PFC and therefore probably do not do great without some safety rails and handholding. In that regard, the debrief may be more dynamic and forgiving. After all, we are expecting someone with minimal training to understand advanced critical care concepts. “You did a great job recognizing the patient needed (intervention). You didn’t catch the (issue). You had to be prompted to start (medication). I would have taken the airway earlier, but then you saw (this), you finally did it.” You can see how, similar to our TCCC article, it’s on a scale of “excellent, needs work, minimum/had to be told.” However, you’re probably not failing medics or pulling them off platoons for not doing well on a PFC exercise like you would a TCCC lane, unless the TCCC aspect is what they messed up on.

The entire purpose of training is to be better. Therefore, ensure to recommend areas they need help and overall themes more than focusing on nitpicky mistakes. Therefore, a sentence to add to the end of the quote above would be, “it’s apparent you aren’t familiar with the CPGs so go over those and have them more readily available. Practice the nursing checklist with your team. Good TCCC in the beginning. Brush up on your (procedure) and head injury medications.” If a medic absolutely fumbles something they should have known or done decently with, then a remedial class on the topic to teach in front of all medics in the unit could be in order. “You didn’t do well on ________, and started it late. I would like you to give a class to me and the other medics on ______.” If there is a procedure they did poorly on, such as a cric, then they likely were prematurely thrown into PFC, and can do remedial hands on training with SEMA and unit Providers.

What would you add?

We hope this guide gives you ideas to help plan or improve exercises at the BN and BDE level. Please reach out if you are a medic or PA who needs help, we got you. If you have ran successful training yourself, please reach out to Ragged Edge or NGCM with how you did it differently so we can add to this article.

Authors:

Paul Loos – Ragged Edge Solutions, Retired 18D

Roger D – Ragged Edge Solutions, Retired 18D

Michael S – 68W3P, NRP

Collin D – SOCM, PA-S

Appendix A: Short lane, limited resources:

“I only have a manikin, and the ability to do a short PCC lane. Is it even worth doing an exercise?”

Manikins should mainly be reserved for ~3-5 hour introductory sessions to get guys used to a basic PCC concepts. This can include some advanced care, planning work-rest cycles, “wake up criteria” and PFC nursing checklists. This is basically the “crawl” to enable them to be more successful for a “walk/run” down the road. You could also do 2-3 manikins if you want to run a BAS PFC scenario as a senior medic and PA for your BN Medics. This also enables more exposure to various pathologies, which means more JTS CPGs.

We provided an example of an introductory scenario:

For the sake of your scenario, feel free to rip out demographic information and substitute your own. This scenario was designed for a treatment team of medics operating out of a Battalion Aid Station (BAS) Role 1 environment. This scenario time was approximately four hours in length with time starting once patients arrived. This was also a part of a much bigger exercise that involved the line medics responding to incidents on the X, rendering initial TC3 care, and utilizing evacuation corridors to move back to the BAS.

Initial Brief: “You are a treatment team assigned to 2-198th CAB BAS. Your team is aware of one incoming casualty after the Scout platoon receives semi-effective fire from enemy forces while conducting screen operations. According to initial reports, you should expect casualty to have significant, possibly life-threatening soft tissue wounds to the left extremity. Estimated time to the BAS is 15 minutes according to the last update. What are your questions?”

The 15 minutes before patient arrival was designed to give the treatment team a moment to huddle and develop their plan. The Treatment NCO was relatively new to his position. This built in time gap, gave him the chance to coordinate efforts with his team, make team assignments, and begin laying out cheat sheets. (Cognitive offload was discussed prior to this event so cheat sheets for things like vent settings, RAVINES, DOPE for airway etc. were developed beforehand).

Patient Arrival: As the evaluator for the PFC scenario, we understand the first 10-15 minutes of receiving the patient can make or break outcomes. Things to stress and emphasize include:

- Proper handoff

- Initiating documentation

- Assessing previous interventions

- Oxygen, IVs, hypothermia prevention, any additional monitoring equipment in place

- Full head-to-toe secondary assessment to identify all injuries

Stabilization: As the initial shock value dies down, our team has identified life threats, reassessed prior interventions, performed a secondary survey to find any missed injuries, and started documentation. The treatment NCO has communicated with the evac NCO that the BAS needs medevac. The initial 9 line and MIST are forwarded through battalion headquarters only to then receive feedback that medevac assets have been delayed. (This was discussed beforehand as it felt more realistic for the battalion, who would be the ones sending our 9 line to Dustoff, to announce medevac capabilities being delayed in lieu of an instructor announcing it from within the BAS). With the news that our patient was traveling nowhere soon, the treatment NCO began assigning additional tasks associated with having to sit on this patient for an extended time period.

Nursing Care/ Advanced Skills: First and foremost your Treatment NCOIC should be establishing timelines, work-rest cycles, and checklists for what needs to be done. This is where the adrenaline portion can take a backseat for the long haul of the training event. Nursing care takes charge over traditional TC3. We have a patient that may need to use the restroom, eat, drink, or even have their bodies worked out a bit to prevent long term bed sores or nerve impingement.

It’s important, at this point of the scenario, to have a plan of how you want the patient to trend. Catalyst moments are given that force your medics to critically think. For example, I had spent a good deal of time with my medics discussing wound tracks associated with high kinetic energy penetrating injuries. In this scenario, I wanted to drive that training home by incorporating a seemingly routine lower extremity gunshot wound that develops into compartment syndrome. So now, as the evaluator, my job is to trend this patient towards that inevitable climax. I had time hacks associated with how the symptoms and red flags would slowly emerge. I had vitals mapped out that would align with whether my medics performed the appropriate treatment, inappropriate treatment, or no treatment at all because they never caught on to the developing situation.

The Breadcrumbs: For this scenario, I started slowly trickling in hints that compartment syndrome may be setting in. As the treatment team evaluated the injured extremity, I would tell them that edema was present and the skin was starting to look pale/ slightly discolored. The patient himself had a note card with answers to questions the medics may ask him:

“It feels like the pain is getting worse and worse”.

“My foot and toes are tingly, like when something goes to sleep”.

“I don’t know how to describe it, my leg just feels tight”.

If the treatment team asked him to move the injured extremity he would act like it was difficult to perform basic range of motion. He complained of feeling weak.

All of these should point the treatment team in the direction of acute compartment syndrome. Keep in mind these breadcrumbs aren’t all happening at once. A PFC lane is more of a slow burn compared to that traditional TC3 lane where everything happens immediately. As the evaluator you entirely control the scenario pace. This treatment team had compartment syndrome fresh on their mind from a couple months ago so, at this point, they picked up on it. If they hadn’t, then I would have piled on a few critical breadcrumbs. The patient would have started complaining of numbness and extreme pain. Upon inspection they may see heavy discoloration and feel tense muscles. Cater this to your own treatment team and always have best case, worst case, and everything in between covered.

Appendix B:

Example Scenario 2: Advanced 24-36+ hour, 1-2 patient(s)

I will now walk you through designing the following scenario which has been ran unit internally. It has two patients, one meant to be a roleplayer, and the other meant to be a high fidelity simulator. Just the longer one can be used, or both depending on how long you want exercise to be and what you want them to test on.

( Example PFC scenario from Google Drive)

Feel free to take this format and swap anything out. Don’t want to test your medics on escharotomy? Remove the burn from the patient and “hour 18 escharotomy event”, then switch the row to another procedure, and make the vitals match. Add the injuries to the initial patient that could later on cause the issue you want to test on. Plug and play, too simple.

On the left column you have vitals and time hacks. This makes it so instructors know what is coming next and when. Next to vitals is wounds and patient presentation, basically what they need to clue medic into or tell roleplayer to do, such as complaining of leg pain.

Past that are common exam finding instructor can offer students only as they assess for it specifically. If they aren’t looking at pupils or doing a neuro, they will not catch a dilated pupil.

The column next to that tells your instructor what interventions you want the medic to do, and pertinent notes such as responses to interventions. “We want medic to use this. After he uses it, patients vitals change to ___”

The last column is teaching points. This is an opportunity to ensure medics walk away with the same pearls briefed by the instructors.

Contingency:

If you start from scratch, you can also have A.I. help make you vital signs for the 12+ hours of your exercise. However, it needs a sanity check because it can hallucinate and create improper wounds, vitals, procedures and indications. We personally recommend making by hand so you are intimately aware of each section. It’s also worth getting another pair of trusted eyes on the scenario(s) before launch. Remember, if you are running two different days of scenarios, you need to have variations so medics who go the first day don’t give away the scenario to those who go the next day. You can still grade them on the same tasks, as well; “Version A gets Anaphylaxis from the blood transfusion, Version B gets Anaphylaxis from a medication pushed hours later.”